Written by Morten Jerven, Department of International Environment and Development Studies

I am very happy to announce that the database on taxation for African countries that covers the whole 20th century is finally ready. Thilo Albers, Marvin Suesse and I have been collecting tax and revenue data on all African polities since the 1890s until the present time.

Before this dataset, the most comprehensive coverage was from the 1980s until today – as described in this article by Wilson Prichard. There has also been some groundbreaking work to present taxation data on the colonial period, such as that by Ewout Frankema and Marlous van Waijenburg who has worked mostly on British colonies. Philip Havik has worked on the Portuguese colonies, and Denis Cogneau, Yannick Dupraz and Sandrine Mesplé-Somps have done comparative work on taxation in the French Empire. Nevertheless, even with all this empirical research over the past decades, and despite the consensus view (namely that taxation is important for development), there are no simple answers to basic questions such as to whether Nigeria taxes more today than it did 20, 30, 50 or 100 years ago, let alone any database that could compare the taxation burden in Nigeria with that of Niger. We can do that now.

One challenge, of course, has been to physically collect all of the data. We have collected data in French, Italian, Portuguese, English and German archives, as well as using national statistical abstracts and IMF reports to obtain data from the post-colonial period. The biggest problem, however, is how to express it comparably across space and time.

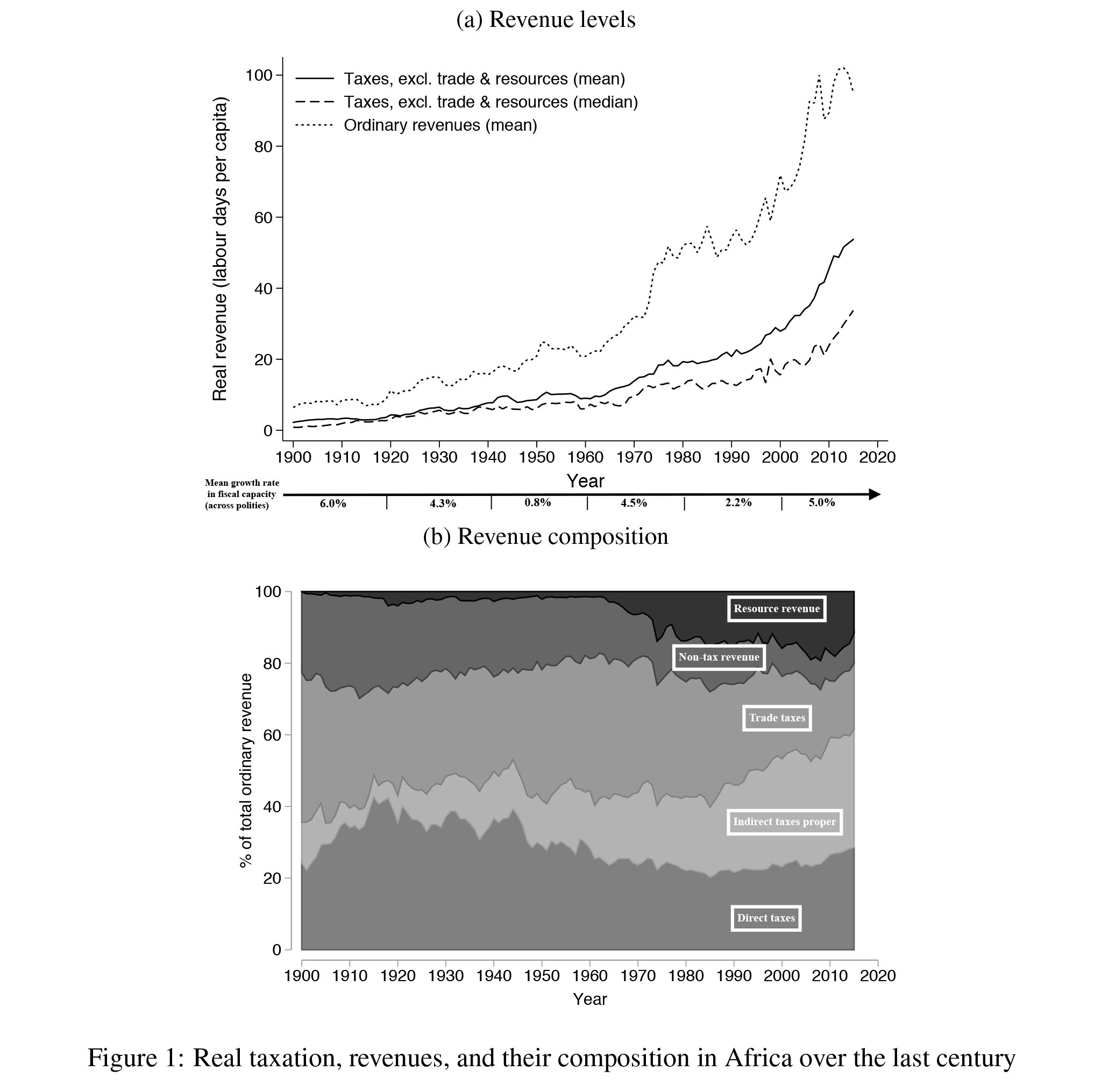

The common summary statistic to express taxation is government revenue as a share of GDP. One problem of this is that GDP is mis-measured for post-colonial times, but the far bigger obstacle is that there are very few estimates of GDP for the period before 1960 (some exceptions). We have therefore collected data on urban, unskilled wages for all polities for all of the country years. When one deflates revenue by daily wages, one gets a readily interpretable expression of real revenue. And so, we can present:

Please read the whole paper, but let me stress a few remarkable things:

- Data availability. The availability of real revenue data on African economies just increased from partial coverage in 1980-2010 and sporadic time series for some countries in 1900-1940 to a complete time series from 1900- 2010. We consider this a major contribution in itself, and since we offer a metric of fiscal capacity across the 20th century, we expect this to be a major resource for other researchers.

- Growth. Fiscal capacity grew more than tenfold. The mainstream approach to African states and taxation is focused on low capacity and stagnation. Our time series challenges that view.

- Direct taxes. Direct taxes are considered hard to collect. Look at the high share of direct taxes in the colonial period. We think it makes the case for re-considering different paths to the ‘modern fiscal state’ in Africa.

- Natural Resources. The stereotypical ‘natural resource curse’ view of the African state is that it depends little on direct tax, and a lot on natural resource rents. This is true only for the recent growth period of ‘Africa Rising’.

- Timing. The perception of “state weakness” originates mostly from the crisis period between 1980 and 2000, neglecting periods of strong growth before and afterwards.

All in all, the paper suggest that the question “why do African states tax so little” might be too reductive and misleading. Thanks to this new dataset we can now explore and test more nuanced theories and research questions.

____________

Morten Jerven is a Professor at the Department of International Environment and Development Studies at NMBU. He has a PhD in Economic History from the London School of Economics and has published widely on African economic development, particularly on patterns of economic growth and on economic development statistics. His books are based on research in Ghana, Nigeria, Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi, Zambia and Botswana.

Morten Jerven is a Professor at the Department of International Environment and Development Studies at NMBU. He has a PhD in Economic History from the London School of Economics and has published widely on African economic development, particularly on patterns of economic growth and on economic development statistics. His books are based on research in Ghana, Nigeria, Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi, Zambia and Botswana.