Welcome to the jungle blog and my first blogpost!

Apparently, the term jungle originates from the Sanskrit word jangala, meaning uncultivated land. However, when most of us think jungle, or at least when I think of jungles, what comes to mind are thick, impenetrable forests or unruly places – like the ominous forests in Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, or the jungle of bureaucracy that I’m presently working my way through to go to the Amazon. After all, getting permission to work in the world’s largest rainforest isn’t all together easy and it took me many rounds with different documents before I finally got my visa through the Brazilian consulate in London. Now I “only” need to register my visa with the Federal Police in Brazil, but that will have be a story of its own.

Even if there is still much to prepare before I may commence my work in the jungle many things have also fallen into place. For example, this blog is beginning to take shape, I have received lots of cool equipment, a crash course in measuring tree heights, and not least, I have arrived on the right side of the Atlantic Ocean. Currently I am in the town of São Paulo where I will spend a couple of days to arrange a few things before flying up to Manaus, the capital of the state of Amazonas, on Monday. It is in Manuas that I will have to sort my visa registration, get some more tools for my fieldwork and arrange my trip onwards into the jungle. But, as my dad’s aunt keeps asking me, where exactly am I going, where will I stay and what will I do in the jungle?

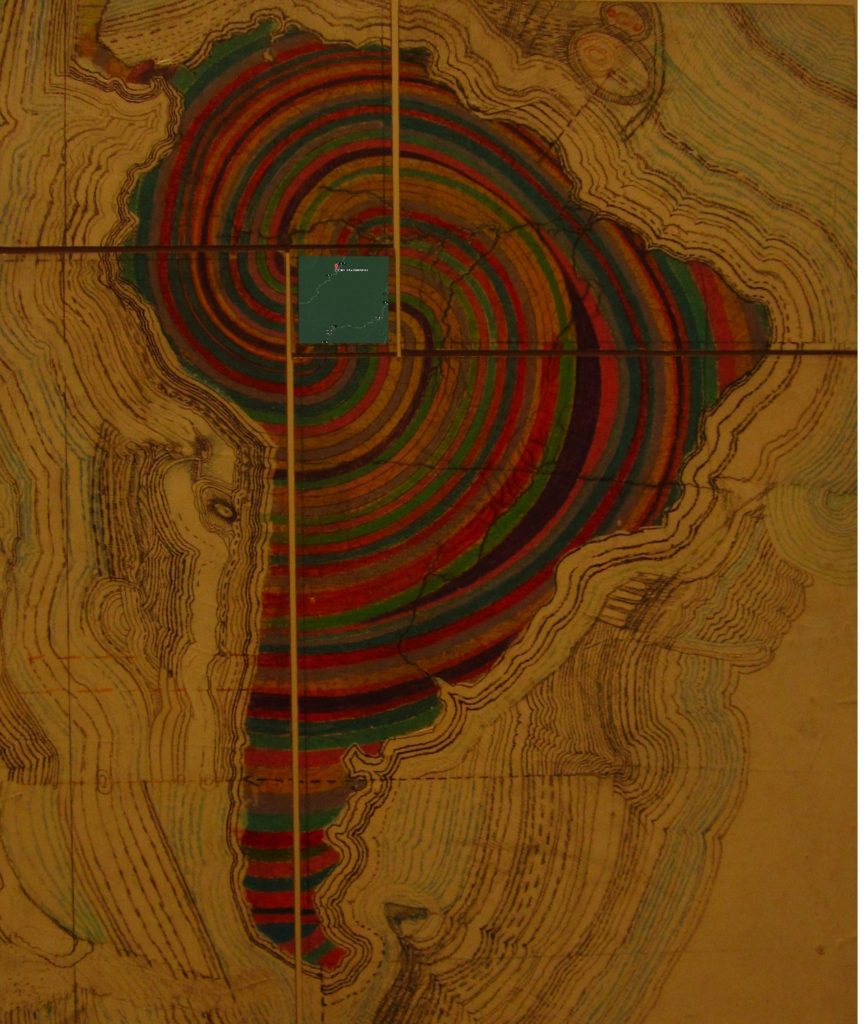

The place I am going to is the river Juruá in northwestern Brazil. The Juruá River originates in the Peruvian Andes and flows north until it reaches and joins the Amazon River in the western part of the Brazilian Amazon. It is along this river, the Juruá, that I will work. To get there I will either have to fly from Manaus to Carauarí, there are two flights a week, on Saturdays and Tuesdays, or there is the option of a five-day boat trip to Carauarí from Manaus. I will probably take the plane to save some time but maybe I will travel back by boat. Regardless, I will most likely have to send some equipment with the boat to Carauarí because the planes are small and there will be limited space for luggage.

From Carauarí I will travel by boat and it is this boat that will become my home. There is a field station where I may spend some time. However, to get to the plots where I will work I will have to travel up and down the Juruá River and most likely, we will go from one place to the next by night. The boat will therefore become my home and I look forward to hang my hammock in the prow of the upper deck. It is like this that we shall sleep, in hammocks with mosquito nettings under a tin roof onboard the boat. A few other people will also come with me to help me in my work. Among them, a botanist will help me identify the tree species that I will work with. Onboard the boat, Senhor Almir will be my skipper and his wife Antonia will be our cook. My dear friend Monica who has previously worked with me in the field will also accompany me to help me count, measure and sample trees and soil. Together we will collect data for me to investigate how much carbon the trees of the floodplains store and thus the contribution of the Juruá floodplain forests to the local and global climate.

You see, in order for trees to get energy and grow, they not only need nutrients from the soil but also take up carbon from the atmosphere, which they store in their wood. In this way, forests help regulate the amount of atmospheric carbon, and since carbon is an important greenhouse gas, the world’s largest rainforest obviously plays an important role in global climate regulation. At the same time, the climate also influences the forest and the forest’s ability to take up carbon from the atmosphere.

In recent years, for example, more frequent extreme weather events in the Amazon jungle have contributed to increased carbon emissions from dying trees and forest fires. In addition, logging of trees has reduced the forests’ capacity to bind atmospheric carbon in the standing wood. Similarly, the development of hydropower projects and selective logging threatens the forests. Development is necessary, but a good management of the world’s largest rainforest also requires us to strive to understand the importance of different types of forests in the Amazon for people and the environment, both locally and globally, as well as to understand the effects of climate change on these forests. That is why I am going into the jungle to study how the natural, yearly flooding events affect the carbon storage of floodplain forests and I invite you to join me on what I believe will be an amazing adventure in one of the world’s most unique environments.

Permalink

Interesting and it will be exciting to read more from you’r fieldwork