Written by Connor Cavanagh, Postdoctoral Fellow, Noragric. This post is one of a series that will explore the aims and conceptual bases of the Noragric-led Greenmentality project.

First published in the Greenmentality Blog.

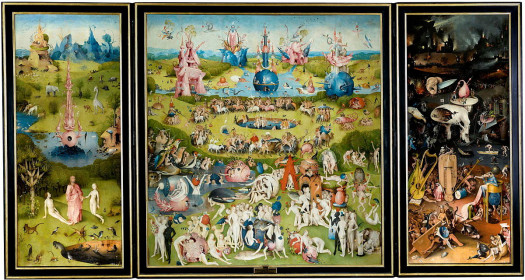

Today, it seems that we all have the environment on our minds. Even Leonardo DiCaprio recently took a break from his alleged philandering and superyacht chartering to intone upon us commoners about the global environmental crisis, resulting in the National Geographic-produced and Netflix-hosted documentary Before the Flood. Waxing poetic on Hieronymus Bosch’s fifteenth century painting, The Garden of Earthly Delights, DiCaprio narrates in the film’s introduction that the Earth is akin to a “paradise that has been degraded and destroyed.” “We are knowingly doing this”, he continues, “I just want to know how far we’ve gone, and if there’s anything we can do to stop it.”

Luckily, it would at first appear, the film presents us with a solution. Golly, there is something we can do to stop it. The billionaire ‘sustainability’ entrepreneur Elon Musk explains this to DiCaprio during a predictably upbeat turn in the second half of the film’s narrative sequence. “You only need a hundred [Tesla] Gigafactories to transition to sustainable energy!”, he exclaims. “Wow, for the whole country?”, asks DiCaprio. “The world … the whole world”, clarifies Musk, not without a touch of exasperation. “That sounds manageable!”, giggles his interlocutor.

Admittedly, this would entail the immediate construction of exactly 98 more of these enormous factories and an almost incalculable profit for Musk, adding to his currently estimated net worth of around 20 billion US dollars. Climate change, their conversation implies, is largely a technical problem with primarily technical solutions: more capital, savvy investments, better technology. Like Musk, why shouldn’t the wealthy position themselves to get rich(er) from the inevitable transition?

Although a sceptic might be inclined to question whether Hollywood actors really possess the necessary authority to lead the fight against the global environmental crisis, DiCaprio is – for better or for worse – well within his rights. At the 2014 UN Climate Summit in New York, Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon designated him as a UN ‘Messenger for Peace’ with a special focus on climate change. Before the Flood is an encapsulation or manifesto of sorts for his preferred response: billionaires, ‘green’ capital, celebrities, international bureaucrats, and the odd liberal-charismatic politician or two UN-ite to deliver us from climactic evil! This is not pure entertainment – it is a message (and a messenger) sanctioned at least in part by our ostensible intergovernmental representatives.

DiCaprio’s film is ultimately fascinating not because of what it ‘says’ – and it doesn’t, in the last analysis, say much at all about environmental change that we don’t already know – but because of exactly what it leaves unsaid. In other words, for what it implies about today’s dominant ‘mentality’ for conceptualizing both the drivers and appropriate solutions to environmental change processes. Films like Before the Flood implore us to do something, man! But they also – and more subtly – shape our understanding of what we can and should do.

These subtle cues – which assist in shaping the values and subjectivities of Hollywood actors and Netflix viewers alike – are to some analysts firmly bound up in the functioning of what the French philosopher Michel Foucault once termed “governmentality.” As far as academic neologisms go, this one can be especially slippery. The critical theorist Jan Rehmann (2016: 150), for instance, contends that the term is one that “sparkles in all directions and whose floating meanings can hardly be determined.” Ouch.

For the less sceptical, the concept is often taken as a portmanteau of sorts for the words ‘governing’ and ‘mentality’, perhaps referring to a prevailing mentality of governing at any given time and place. This interpretation has notably been resisted by Michel Senellart, however, who edited the text of Foucault’s Security, Territory, Population course in which the term first appeared. As Senellart (2007: 399-400) puts it:

Contrary to the interpretation put forward by some German commentators […] the word “governmentality” could not result from the contraction of “government” and “mentality,” “governmentality” deriving from “governmental” like “musicality” from “musical” or “spatiality” from “spatial,” and designating, according to the circumstances, the strategic field of relations of power or the specific characteristics of the activity of government.

Etymology aside, Foucault (2008: 186) himself would soon offer a much more concise definition in the following year’s Birth of Biopolitics lectures, referring simply to “what I have proposed to call governmentality, that is to say, the way in which one conducts the conduct of men.”

Even with this simpler definition, why bother with a term whose meaning is apparently so elusive? Our current anti-intellectual zeitgeist might suggest that we should not. Yet I think there are at least three good reasons for an engagement with the concept.

First, particularly in the Birth of Biopolitics lectures, Foucault leaves us with a sense that ‘governmentality’ comes in many varieties, and might be directed at many targets. It can refer to government not only of and by the state, but also government through the family, the physical environment or milieu, the market, the community, or the individual. Perhaps, even, through Netflix. This is useful, as it reminds us that both ‘who’ the subject of government is and ‘how’ they should be governed varies greatly across histories and geographies. In other words, the concept of governmentality is not monolithic, but rather must be inductively constituted on the basis of empirical detail in any given time and place. To do so within our present – though doubtlessly asymmetrically experienced – conjuncture will inevitably be a core task of the Greenmentality project.

Second, the concept invites us to consider the ways in which government is not merely something that is done ‘to’ people (or to the nonhuman environment, for that matter), but is also something that people (and perhaps also nonhuman subjects, see Srinivasan 2014) are invited to ‘do’ to themselves. DiCaprio’s film, for instance, tells us as much about how he has himself apparently desired to become a good subject of contemporary forms of ‘green’ governmentality rooted in ‘sustainable’ capitalism and international bureaucracy as it does about actual processes of environmental change. Perhaps this is simply to feed his ego or to abate his environmental guilt for routinely chartering some of the world’s largest and most unsustainable yachts, for example, or his apparent penchant for extensive travel in private jets. But it is in many ways also an injunction to the viewer: to participate in the rectification of environmental change through the intensification of capitalism rather than via its opposition.

Finally and relatedly, as Timothy Mitchell (1990) once famously noted in relation to his own notion of “enframing”, Foucault’s works complicate our understanding of ‘resistance’ and its presumed opposition to particular forms of power or domination. For example, a conventional account of resistance might conceive of it as a form of agency exercised in opposition to a particular mode of governing, whether overtly or more subtly, as in the works of James Scott (1985) on ‘everyday resistance’ and the ‘weapons of the weak’. Crucially, however, people can also be governed to resist in certain ways rather than others. Classically liberal forms of governmentality, for instance, might accurately be construed as encouraging certain forms of protest and critical free speech, given that the legitimacy of the former is in turn enhanced when people engage in these activities. Likewise, a sympathetic reading of Before the Flood might suggest that DiCaprio and his allies are ‘resisting’ a business as usual form of environmentally ruinous capitalism. Yet we are increasingly being invited to participate in precisely such practices of ‘resistance’, if we can truly call them that, as both states and capital actively seek assistance to ‘green’ themselves in profitable ways.

As Foucault (1982: 790) put it in another oft-cited definition: “[T]o govern […] is to structure the possible field of action of others”. Today, our possible field of action is increasingly being foreshortened to render unimaginable the very possibility of reckoning with processes of global environmental change in ways that might disrupt prevailing interests and constellations of states, capital, and transnational bureaucracies. Whatever their flaws, films like Before the Flood are merely a symptom of that trend. True resistance, today, is first and foremost an act of imagination – of daring to conceive of a world characterized neither by ecological despoliation nor the vast inequalities that contemporary forms of capitalism produce. To resist, in other words, is simultaneously to insist on the myriad possibilities for greening and governing – or being ‘greened’ and governed – otherwise.

References

Foucault, M. (1982). The subject and power. Critical inquiry 8(4): 777-795.

Foucault, M. (2007). Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the College de France, 1977-1978. New York: Picador.

Foucault, M. (2008). The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the College de France, 1978-1979. New York: Picador.

Mitchell, T. (1990). Everyday metaphors of power. Theory and society, 19(5), 545-577.

Rehmann, J. (2016). The unfulfilled promises of the late Foucault and Foucauldian ‘governmentality studies’. In D. Zamora and M.C. Behrent (eds), Foucault and Neoliberalism. London: Polity Press., pp. 146-170.

Scott, J. (1985). Weapons of the weak: everyday forms of peasant resistance. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Senellart, M. (2007). Course context. In M. Foucault (auth.), Security, Territory, Population: Lectures at the College de France, 1975-1976. New York: Picador., pp. 369-401.

Srinivasan, K. (2014). Caring for the collective: biopower and agential subjectification in wildlife conservation. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 32(3), 501-517.

Follow more blog posts from this project at the Greenmentality webpages.

Connor Joseph Cavanagh is an environmental social scientist with a main focus on political ecology, environmental governance and agrarian studies.

Connor Joseph Cavanagh is an environmental social scientist with a main focus on political ecology, environmental governance and agrarian studies.