Noragric PhD Fellow Tomohiro Harada on the UN’s recent Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform in Bonn.

Indigenous peoples are no longer ’observers’ at the UNFCCC. As effective ’contributors’ to shaping the plans for the Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples’ Platform (The Platform), Indigenous Peoples have unprecedented opportunities to enhance their participation across UNFCCC processes. So what happens now?

A new alliance

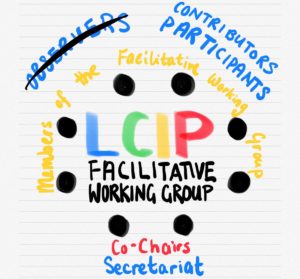

At COP24 in Katowice, the Parties passed a landmark decision to establish a Facilitative Working Group (FWG) of the Local Communities and Indigenous Peoples Platform (LCIPP). The establishment of this group, whose mandate is to create a work plan for the LCIPP and implement its functions, is historic in the context of indigenous movement. It constitutes the beginning of a new partnership with the Parties, based on the principles of equal status of indigenous peoples and Parties, including in leadership roles. Furthermore, the Platform enhances indigenous peoples participation and visibility in UNFCCC’s processes.

For the indigenous peoples, the Bonn Climate Change Conference (SB50) started with the gathering of 13 FWG members, six from the Parties and seven indigenous peoples, as well as other indigenous peoples and Parties interested in the Platform. The first task of the FWG was to develop a two-year work plan for the Platform to be decided by the Parties at the COP25 in Santiago, Chile.

During this meeting, I witnessed the extraordinary process of Indigenous Peoples’ direct contribution to crafting the activities of the LCIPP, as the FWG took an inclusive, open and transparent approach to the development of the work plan. Every idea was considered and reflected in the first draft of the work plan during the meeting. What was also interesting to observe was the layout of the meeting room, which resembled the setup from the Talanoa dialogue, an indigenous way of conducting open, inclusive and transparent dialogue. This may be interpreted as a way of indigenising the conversation on climate change, to help build a relationship with the indigenous peoples. It seemed that the ‘Observer’ tags around the necks of these people no longer characterized their identity in the UNFCCC. The only observer of course, was me, observing the meeting for research purposes. The work plan remains a work in progress at the time of writing.

In the context of UNFCCC, the Platform is one of a number of constituted bodies within the Convention. Others include the Adaptation Committee and the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage. These bodies provide advice and expertise to advance the implementation of the Convention, the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement. In practical terms, this not only puts the Indigenous Peoples and the Platform on a radar within and outside of the Convention, but also means that the Platform and by extension, Indigenous Peoples, are now invited to collaborate across various constituted bodies both within and outside the Convention to provide inputs to their respective activities.

What happened to the Spirit of Paris? Indigenous Peoples at COP24 in Katowice, Poland

As the Platform appeared on the radar of the SB50, the response by other constituted bodies was immediate. In the first workshop, a number of constituted bodies within the Convention showed a great deal of interest in the Platform. At the second workshop on collaboration with bodies outside of the Convention, a variety of actors such as UN Specialized Agencies, charities, and universities, offered their ideas for synergy with the Platform. What these interactions indicate is that the work of FWG extends far beyond the implementation of the functions of the Platform. As a constituted body, the recognition also brings about new opportunities for Parties to encounter and understand the value of traditional knowledge, as well as the requirement for Indigenous Peoples to engage effectively with a variety of actors on themes ranging from adaptation and mitigation, technology, methods and observation to loss and damage.

Meanwhile, important discussions continue amongst Parties at SB50. The language of human rights – including those of indigenous peoples – still remains bracketed (i.e. not agreed upon) in many of the key draft texts under consideration, such as on the implementation of Article 6 of the Paris Agreement. Recalling that the Platform is only as strong as the degree to which various decisions by the Parties respect human rights and the rights of indigenous peoples, there remains significant work ahead in terms of lobbying the Parties, in unison with other actors advocating a rights-based approach to climate policy and action. Equalization and protection of indigenous peoples’ knowledge is an important aspect of Indigenous Peoples’ diplomacy in this context.

Indigenous Peoples embody 80% of the world’s cultural and biological diversity

For the last five years, indigenous peoples have made great sacrifices to contribute to the UNFCCC, taking time away from their families and communities to travel around the world, in order to create a permanent space for indigenous peoples and to get the Platform off the ground. This achievement cannot be underestimated, though everyone knows that this is only the beginning.

Significant work lies ahead in terms of getting the Parties to agree on a more ambitious and bold target to address the adverse effects of climate change. Even more difficult challenges lie ahead for indigenous peoples in attempts to sway the Parties to safeguard their rights. The recognition of indigenous peoples’ rights enhances their capacity to take care of their environments using their own knowledge. We mustn’t forget that indigenous peoples embody and nurture 80% of the world’s cultural and biological diversity.

Just the beginning…

Progress will require close and transparent collaboration between the Indigenous Peoples Caucus and the FWG, so as not to create a disconnect within Indigenous Peoples at the UNFCCC. Indigenous Peoples may now be required to look beyond the Platform in order to cover the gaps as they appear as a consequence of the establishment of the Platform, and the immediate expansion of Indigenous Peoples’ possibilities at the UNFCCC. The Platform opened up many spaces for Indigenous Peoples at the UNFCCC to take their voices beyond the plenary sessions and interact with the Parties to build mutual understanding. It is still unclear how it will pan out, but one thing is certain: everyone is watching.

Tomohiro Harada is a PhD Fellow at the Department of International Environment and Development Studies, focusing on indigenous diplomacies in global politics, specifically Sami diplomacies in global environmental politics.