Landscape architects’ involvement in the building of hydroelectric power stations and the related large-scale landscape projects since the 1950s marks the shift of the discipline from garden architecture to landscape architecture in Norway. Knut Ove Hillestad (1924 – 2005) and Toralf Lønrusten (1936-2014) are two representatives of this transitional period.

Power poles in Vassbygdi, Aurland. Picture taken by Knut Ove Hillestad in 1982 (NVE Photo Archive)

Power poles in Vassbygdi, Aurland. Picture taken by Knut Ove Hillestad in 1982 (NVE Photo Archive)

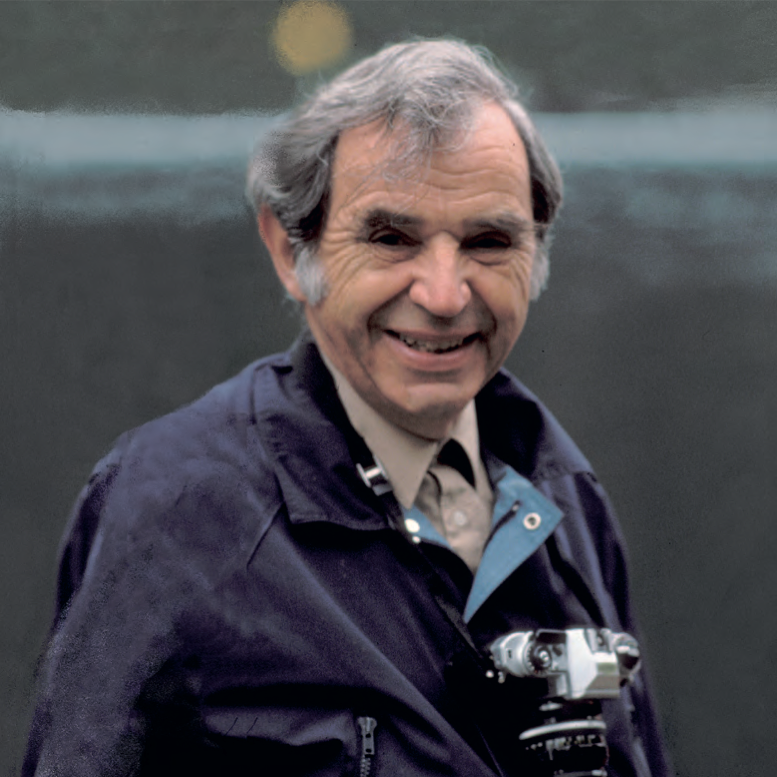

Knut Ove Hillestad – first landscape architect in a homogenic engineer topic

The Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate (Norges vassdrags- og energi direktorat, or NVE) was responsible for the first hydroelectric power stations built after WWII in Norway. NVE established a landscape department at the beginning of the 1960s. The garden architect Knut Ove Hillestad had been the head of the department and had represented landscape and environmental interests (especially focusing on natural protection issues) for 30 years since his first employment by NVE in 1963 (Jørgensen 2011).

Knut Ove Hillestad was trained as a garden architect at Norwegian Agricultural University in Ås (NLH; now Norwegian University of Life Sciences, or NMBU) from 1950 – 53. He started his carrier with teaching horticulture at Sogn horticultural school (Sogn jord- og hagebruksskole), and continued at State Gardener School (Statens gartnerskole) in Grimstad. After graduation from NLH, it took a few years before Hillestad got a permanent position as county gardener (Fylkesgartner) in Vestfold. One year after, he moved again and worked two years as secretary in Oslo city architect office, and then worked in Kristiansand park authority between 1956-63. In Kristiansand, he was engaged in several disputed cases where entrepreneurs wanted to develop and build without any consideration of nature and recreational issues. He advised in such cases, “it is about working with nature and not against it” (Nilsen 2010). For Hillestad, it was important to keep and preserve the natural terrain and the existing vegetation.

Knut Ove Hillestad (in Nilsen 2010)

In the 1960s, the projects under the commission of NVE were under high pressure. The state-owned heavy industries needed electric power to run the aluminium production. From the 1960s until the 1990s, there had been a major increase of hydropower stations in the country. Meanwhile, the society began to aware the contradiction between the hydropower development and the nature conservation. The case Uste-Nes in Hallingdal was one of the first projects where natural, touristic and industrial interests needed negotiation. The company Oslo Lysverker (now E-CO Energi) applied for developing waterfalls into a hydroelectric power stations, which would have a huge impact not only on the environment, but also on tourism and local fishing. Tourism was the third largest export industry in Norway at that time. After long-time negotiations among different stakeholders, Oslo Lysverker received permission in 1962 to carry on the project, while NVE was asked to control and guide the construction plans of Uste-Nes and following projects. Therefor there was a need to employ a landscape architect in NVE (Nilsen 2010). The director of NVE Hans Pedersen Sperstad (1917-1986) had close contacts with representatives from the Norwegian Association of Garden Architects (later Norwegian Association of landscape architects). It seems that the association helped NVE describe the suitable profile for this position, and underlined this was a potential market for future landscape architects in Norway (Nilsen 2010).

When Hillestad started at NVE, he did not have much knowledge in nature conservation, neither was he in contact with relevant organisations in tourism or recreation. However, he noticed the ugly and unattractive places that hydropower industries had created in the landscape, and was ready for a change. In an interview with the local newspaper, he said, “preventing Norwegian mountains and valleys from being harmed by good engineers is really a different type of task than decorating gardens in Horten.” (Newspaper Nationen 06.06.1964 in Nilsen 2010).

Until then no Norwegian landscape architect had been involved in large landscape interventions or nature impact assessments of such scale. The working environment of Hillestad was dominated by engineers, who seemed to be ‘rougher’ than the garden architects. In addition, the contents of Hillestad’s work was rather unfamiliar to his colleagues in NVE. They teased him by saying, “this is the guy who should teach us how to plant roses on the stone dumps”. Hillestad replied, “we could start with balcony boxes on the dams” (Nilsen 2010).

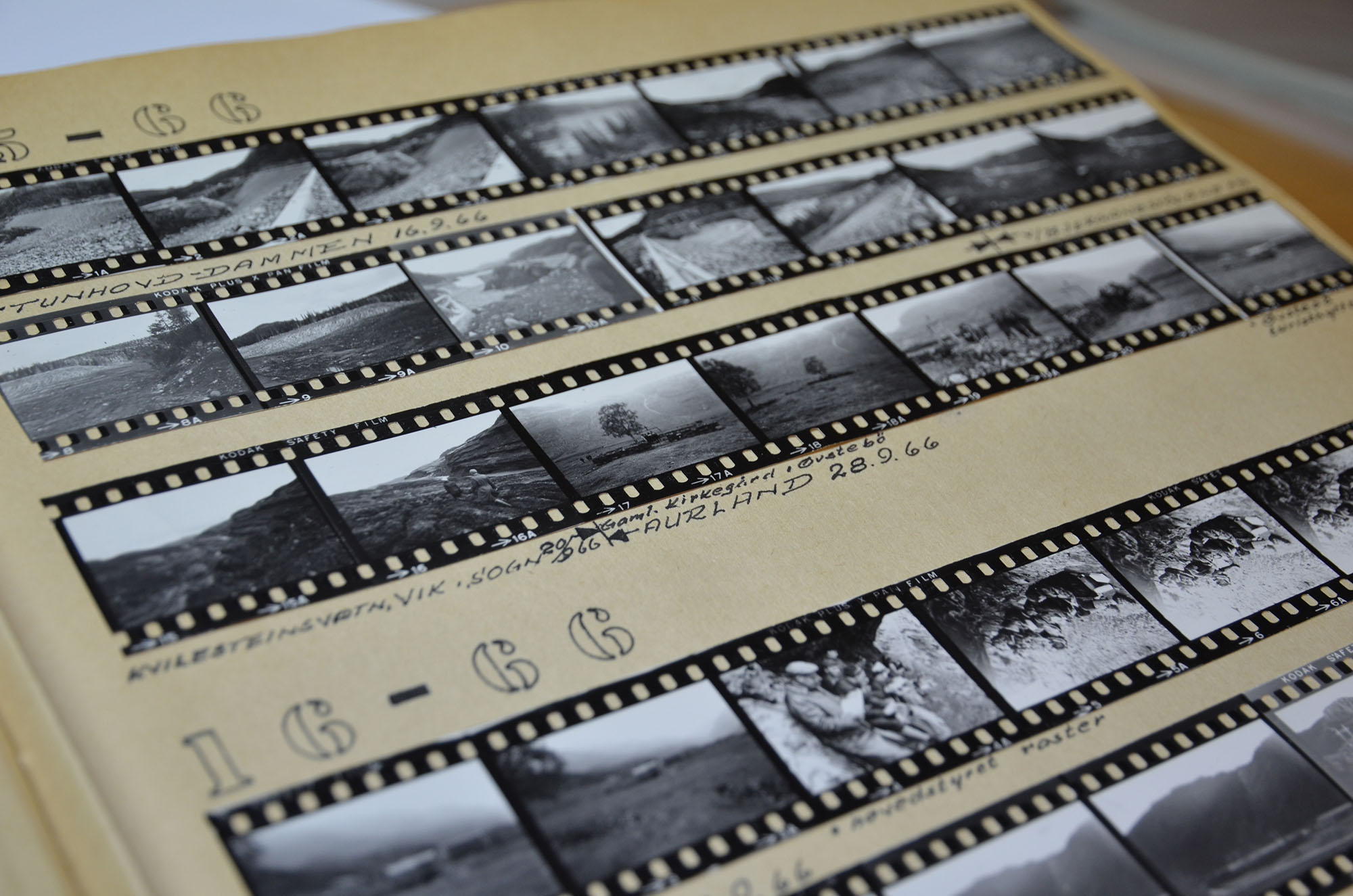

A large photo archive of Knut Ove Hillestad, documenting several hydroelectric power stations in Norway before and after realisation, is stored in the NVEs headquarters in Oslo.

At the beginning, Hillestad worked closely with Swedish colleagues. He quickly built up valuable knowledge about hydroelectric power stations and how the negative impacts could be minimised on the landscape and the people. In addition, he established important links with experts from nature conservation and tourism. Hillestad also used different expert groups at NLH, for instance the Department for dendrology and plants, to start experimental plantations on stone dumps and infrastructures in hydroelectric power stations. They observed the ecological succession of such areas and impacted it by adding soil or plants to get satisfactory results (Nilsen 2010).

Hillestad contributed to the protection of natural and cultural values through regulations that defined minimum water flows, the establishment of operational thresholds and a wide range of other measures. He also published several books related to his work. These efforts highlighted the values of garden architects in a new field, and contributed to expanding the profile of the profession both at the NLH and in the broader society (Jørgensen 2011).

Toralf Lønrusten and Aurland Hydroelectric Power Station

Aurland Hydroelectric Power Station was one of the major projects conducted by the company Oslo Lysverker (today E-CO Energi). E-CO Energi, owned by the City of Oslo, is a Norwegian power company and after Statkraft the second largest producer of electricity in Norway. The project in Aurland started in 1965 and had lasted for almost 20 years (Bruun 2004).

In March 1969, Oslo Lysverker received the license for developing the Aurland waterfalls into one of the largest hydroelectric power stations in Norway. The project indicated a shift of the meeting point between power industry development and nature conservation in Norway. Due to society’s increasing awareness of nature protection in industrial development, the landscape issues had more weight in this project.

The massive expansion of hydroelectric power stations in the country led to the resistance in local communities against those projects. The new Nature Conservation Act of 1954 opened the door to the protection of valuable landscapes, and increased the conflict between development and conservation (Jørgensen 2011).

Field trip to Aurland in August 1967. From left: director of NVE H. W. Bjerkebo, farmer Olav Benum, Members of Parliament Torstein Selvik, Nils Jacobsen and Bernt Ingvaldsen and agricultural manager of the county Trygve Haugeland (NVE Photo Archive)

Field trip to Aurland in August 1967. From left: director of NVE H. W. Bjerkebo, farmer Olav Benum, Members of Parliament Torstein Selvik, Nils Jacobsen and Bernt Ingvaldsen and agricultural manager of the county Trygve Haugeland (NVE Photo Archive)

Aurland hydropower project encountered large scepticism in the local community and especially by nature conservation experts. NVE was the authority to approve the plans with the consideration of different opinions. NVE advised Oslo Lysverker to survey the natural values of the valley before a concession for exploitation could be given. The goal was to minimize the impacts on the landscape in advance (Eie 2016). During this process, two parties with different opinions were formed: on the one side, the municipality wanted to build a good road connection crossing the mountains into the valley (Aurland had no road before 1960); on the other side, the nature conservation people had an interest to minimize the impact as much as possible. In order to meet the demands of both sides, Oslo Lysverker engaged the landscape architecture company Aasen and Lønrusten. Toralf Lønrusten therefore became another important landscape architect that had great impact on hydroelectric power stations in Norway.

Toralf Lønrusten graduated from NLH in 1963. When he was a student, Lønrusten was interested in conservation and wrote a thesis on hydropower. In 1965, he was contacted by Hillestad, who recommended him to work on the Aurland hydropower project for NVE. Lønrusten accepted the commission. When finalising the contract, Hillestad noted that it was landscape architects rather than garden architects that were more qualified in this type of large-scale project (Jørgensen 2011). In 1966, Lønrusten together with Bjarne Aasen bought the company Morten R. Grindaker and changed its name to Landscape Architects Aasen and Lønrusten A/S. The office was the largest and the most innovative at that time in Norway (Bruun 2004).

The plans for Aurland Hydroelectric Power Station changed significantly during the process. Due to the involvement of landscape architects, the impacts of the project on the landscape were reduced, especially those related to the road construction and large high voltage lines. The location of the main dam Aurland I was changed to reduce the visual exposure in the landscape. The plan of one large dam Aurland III was replaced by several smaller water reservoirs. In addition, there was a strong focus on the water supply in the valley in wintertime.

Aurland I in 1967. Picture taken by Knut Ove Hillestad (NVE Photo Archive)

Aurland I in 1967. Picture taken by Knut Ove Hillestad (NVE Photo Archive)

In retrospect, Aurland Hydroelectric Power Station has been seen as a breakthrough project in relation to landscape protection. Its selected strategies to safeguard landscape in large-scale construction projects include detailed design, landscaping and the follow-up of landscape interventions. The valley of Aurland has largely retained its attractiveness as a recreation area, thanks to the successful and consistent implementation of comprehensive landscape strategies done by Knut Ove Hillestad, Toralf Lønrusten and their colleagues.

In 2019, it will have been 50 years since the license for Aurland hydropower project was given. In 2019, it will also have been 100 years since the first educational programme in landscape architecture (then called garden architecture) established in Ås.

From garden architecture to landscape architecture

In 1966, when Lønrusten changed his office name to Landscape Architects Aasen and Lønrusten A/S, the title Landscape Architects clarified that this new generation was not decorating architectural or engineering projects. Hillestad and Lønrusten wanted to influence and improve the large-scale landscape projects by being involved from the beginning. Landscape architects should guide the technical approaches into a new way of thinking. Esthetical, functional and recreational concerns were combined with natural protection issues. Lønrusten developed those ideas also within the Association of Norwegian Landscape Architects, where he had been actively involved since 1964. In 1969, the association changed its name from the Association of Norwegian Garden Architects to the Association of Norwegian Landscape Architects. Lønrusten actively fought for this change.

During the 1960s and the 1970s, admissions to the study programme at NLH quadrupled and the resources of the department increased. Interests in environmental studies and nature conservation started to grow in the academic community (Jørgensen 2011). At the same time, the educational programme in Ås changed the name from garden architecture to landscape architecture, which opened up new missions of this discipline. Nature conservation has since then been one of the major topics of the programme. Current courses such as “Roads and Railways in Landscape” (LAA310), “Strategical landscape planning” (LAA360) and“Landscape ecology” (LAA370) are the result of this transition. The discipline actively reshaped itself to respond to the new requirements of the society. The reasons for the transition are probably multifold, while involving landscape architects in building hydroelectric power stations was a powerful start.

References

Magne Bruun: 75 år for landskap og utemiljø. NLA 2004.

Karsten Jørgensen: “Landscape architecture in Norway: a playful adaptation to a sturdy nature”. Web, www.researchgate.net [April 2011].

Jon Arne Eie, Miljøhensyn inn i norsk vassdragsforvaltning 1963-2014. NVE, Rapport nr. 52-2016

Yngve Nilsen. Landskapsarkitekten Knut Ove Hillestads virksomhet ved NVE 1963-1990. NVE Rapport 21-2010

The photo archive of Knut Ove Hillestad is stored in the NVEs headquarters in Oslo, while most of the written documents concerning concessions for hydroelectric power stations from NVE are in the National Archive of Norway, Oslo.

The archive of Toralf Lønrusten is stored in the Historical Archive of Norwegian Landscape Architecture. A list of projects in this archive can be found here: Fq. Toralf Lønrusten.

Permalink

Permalink

There is so much useful information contained in this post. Really smart witty way to say things. I really appreciate it. I will check back later for more great content. I also found some other witty material here https://conservationconstructionofdallas.com/. I can’t wait to read more in the future. Thanks again.