The collection of Pål Sæland (1897-1979)

Planning and designing cemeteries and graveyards became a new task for garden architects in the early 1900s. According to professionals such as Olav Moen (1887-1951), Pål Sæland and Karen Reistad (1900-1994), cemeteries in Norway were in a “sad condition”. Only some of the larger municipalities employed trained professionals while most of the plans and the maintenance of cemeteries were carried out by unskilled people. When the Department of Garden Art (now the Department of Landscape Architecture) at the Norwegian Agricultural University College in Ås (now Norwegian University of Life Sciences) was established in 1919, one of its tasks was to educate cemetery planners, like what Olav Moen recommended in 1921 “churchyard art as a separate topic in garden art” (Moen 1922).

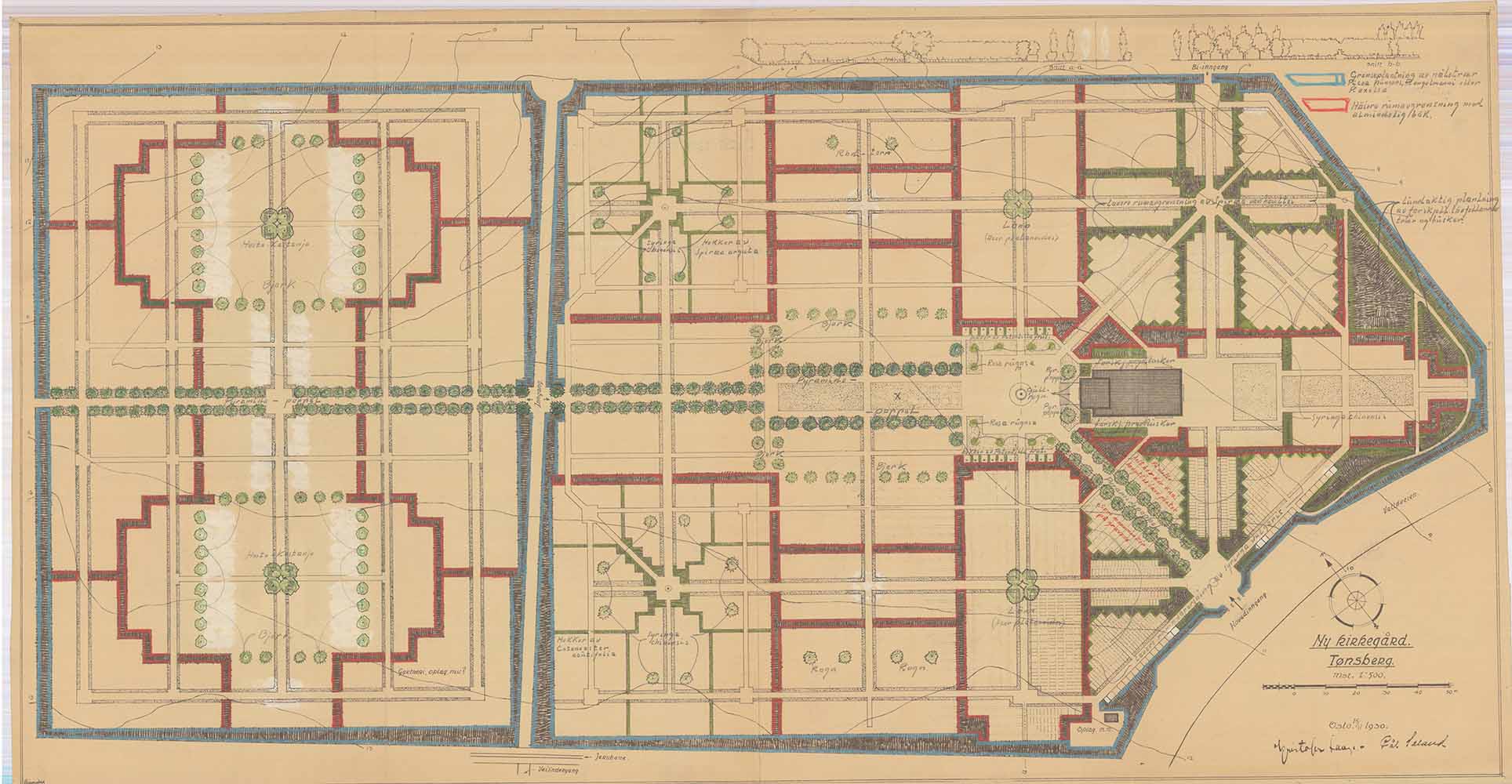

Tønsberg cemetery was designed by Pål Sæland. Photo: Kirsten G. Lunde

Tønsberg cemetery was designed by Pål Sæland. Photo: Kirsten G. Lunde

Pål Sæland was one of the first garden architects educated in the new program in Ås. He graduated in 1924 and started working at Oslo Park Administration (Oslo Parkvesen) at the office of the city gardener Marius Røhne in Oslo. In 1925 he studied for one year in the US. Back in Norway he continued his work in Oslo Park Administration. Between 1930-46, Sæland was employed as garden architect in the Church Administration (kirkeverge) of Oslo and continued as “Gravlundsjef” (director of cemeteries) from 1946 until his retirement in 1967. Sæland was responsible for the cemeteries of Oslo, as well as projects in the South and East of Norway (Jørgensen 1995). One of his major works was Vestre Gravlund burial ground for urns from 1934.

Pål Sæland 1926. Photo: private

From 1948, Sæland was responsible for teaching the topic in Ås. In the same year, Sæland became the first cemetery consultant working for the State (Statens kirkegårdskonsulent). In the beginning this was only a part-time position. However, he and his successors managed to make a large impact for the cemetery culture in Norway.

In the early 1900s, there was an increasing demand for new cemeteries in the cities. In 1931, Sæland recommended the establishment of forest cemeteries. Forest cemeteries take advantage of natural situations and terrain. The cemeteries appeared as a park or a grove. Existing forests were carefully cleaned with graves in-between. According to Sæland, it would be no problem to find good areas for forest cemeteries in Norway (Sæland 1931). However, it took another 20 years before the first forest cemetery in Norway established in Borgestad in Skien, planned by Karen Reistad in 1955/56.

Cemetery planning is a challenging topic. In addition to a good master plan for the entire cemetery, one must provide graves in rational sizes and forms. The cemetery should be seen as one unit instead of a number of more or less maintained and randomly placed graves (Reistad in an interview for Fylkestidende in 1954).

Tønsberg’s new cemetery is a comprehensive plan made by Pål Sæland in the 1930s. The plan shows an excellent example how vegetation, paths and graves are composed—an art almost forgotten today. A main axis of pyramid poplar leads to the chapel square, and beech hedges form the the overall layout. The smaller rooms within were planted with lilac and Spirea vanhouttei. Sæland points out that the entire planting must be realised before the cemetery is taken into use. The plants need some years before they create a worthy frame (Sæland 1936, Letter to the gardener, ILA archive).

Plan for Tønsberg cemetery 1930, Pål Sæland

Plan for Tønsberg cemetery 1930, Pål Sæland

Sæland wanted “memory groves where nature itself is the great living memorial” (Sæland, undated manuscript of a lecture, ILA archive). The formation of the rooms within the cemetery was important. It separates different grave types and creates the necessary privacy for visitors. It also gives the illusion that the cemetery is moderate in size, even though it is relatively large. In order to get a variation, the hedges were cut in different heights.

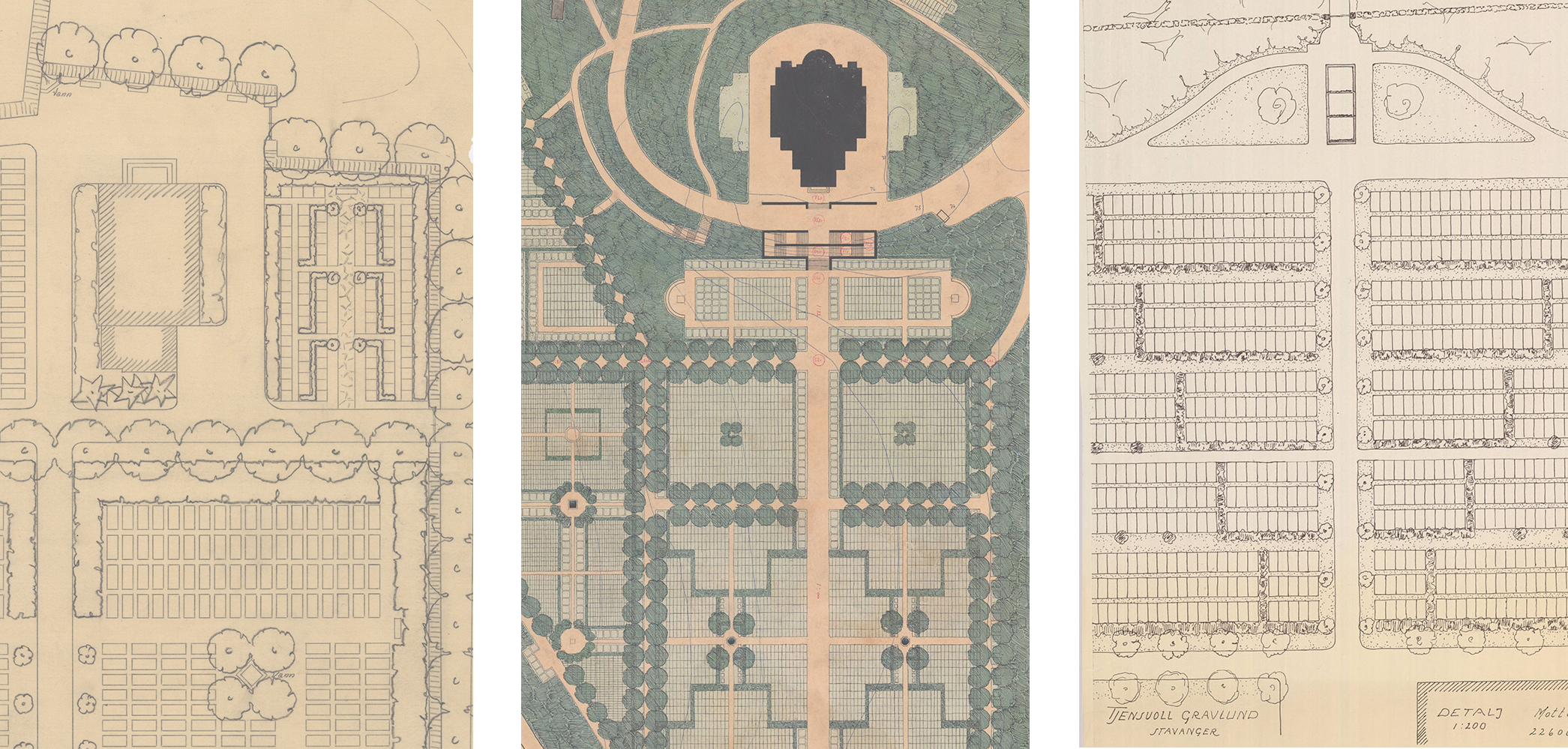

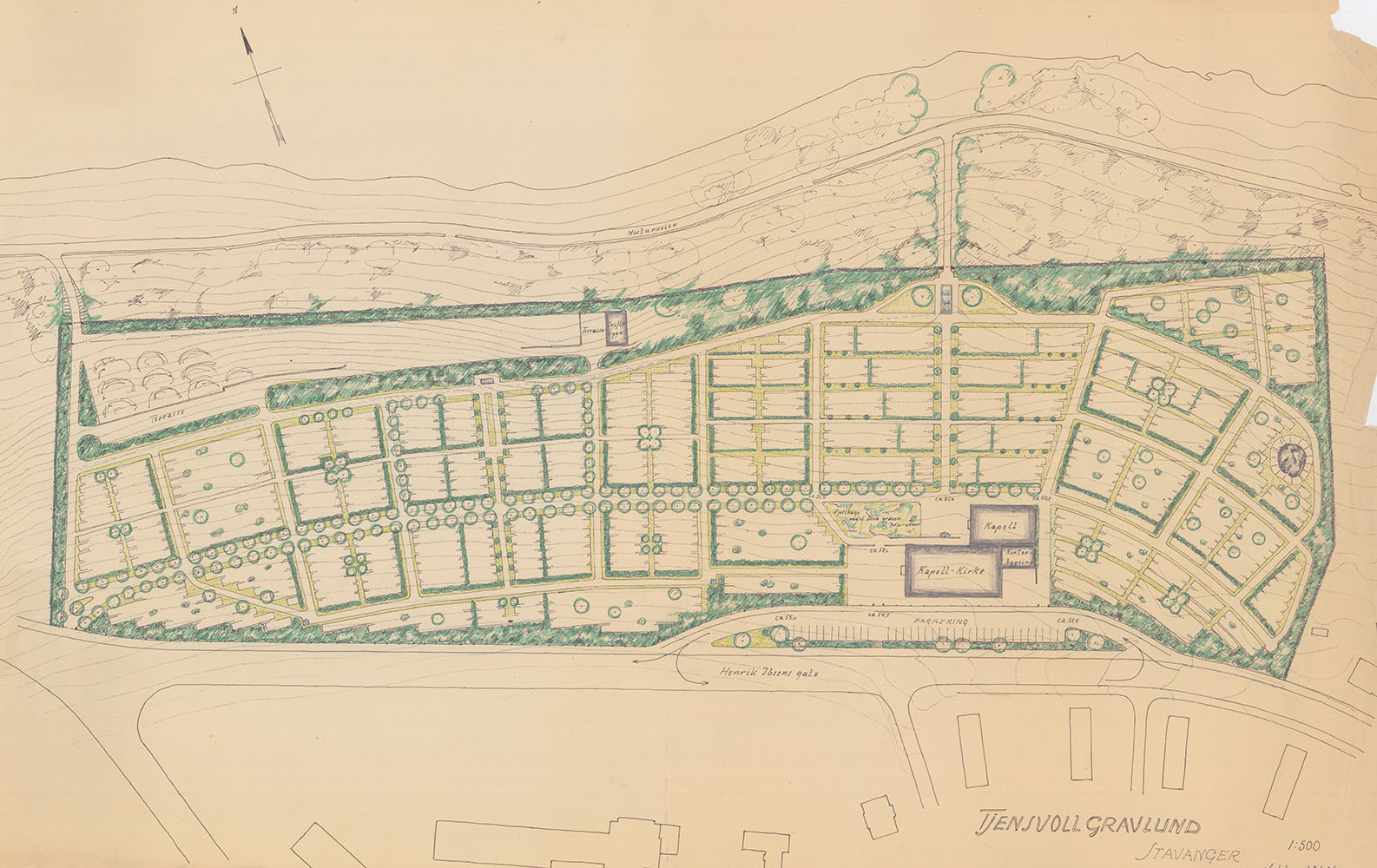

Details of Vang (1944 and realised soon after), Ullern and Tjensvold cemetery (both from end of 1950s are not realised) show how Sæland created different rooms with hedges.

Details of Vang (1944 and realised soon after), Ullern and Tjensvold cemetery (both from end of 1950s are not realised) show how Sæland created different rooms with hedges.

While working with cemeteries in Norway, Sæland often encountered “skikk og bruk” (custom and usage) or the tradition of “we continue as (what we have done) before”. Modernism was not desired in the graveyard culture. However, Sæland argued, “it is quite certain that a little more reflection and critical assessment would lead to better results, like in many other areas” (Sæland 1937).

Existing customs and practices such as using earth mounds or stone frames to mark single graves, building large grave monuments and selecting inappropriate plants are a challenge for contemporary garden architects. Too many gravel paths inside the graveyards look like “open wounds” (Skadsheim 1946). Access to the graves should preferably be realized with small and medium-sized flagstones (Sæland 1938). “Nothing can be more worthy than the cemetery forming a continuous grass slope with the graves like little flower beds in it” (Sæland 1931).

Together with a master plan of the entire cemetery, Sæland always recommends rules for the design of single graves (Sæland 1931). Good craftsmanship is crucial. At that time, “cheap factory goods” (Sæland 1931) and “mass production” (Skadsheim 1946) in the cemeteries were deplored by several professionals. According to Sæland, it does not matter to get the monument as high, wide and massive as possible; instead, “it is the shapes, the symbols and the craftsmanship that makes a graveyard beautiful” (Sæland 1938).

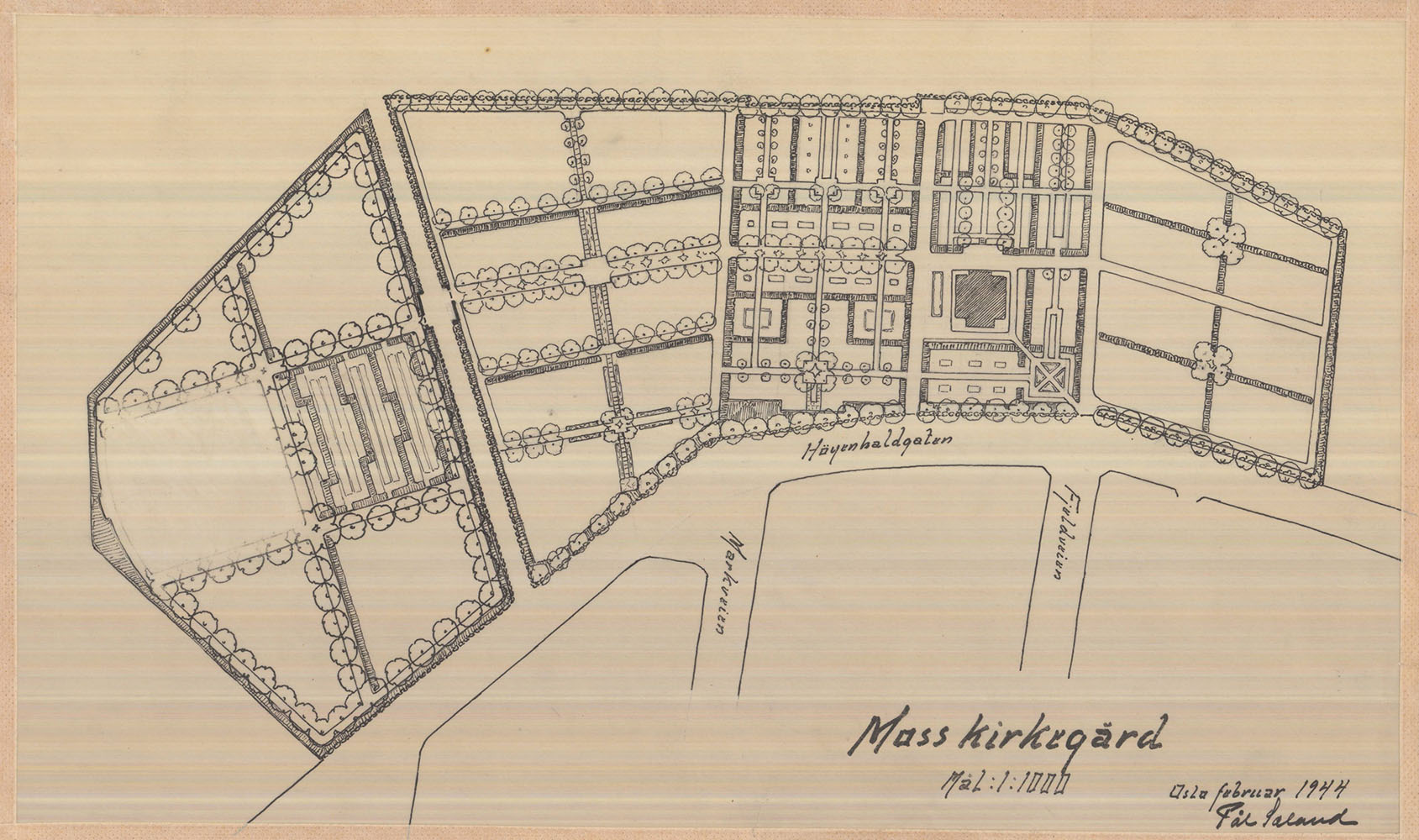

Moss cemetery 1944, Pål Sæland

Moss cemetery 1944, Pål Sæland

The plans for Moss Cemetery in 1944 show how Sæland utilised the potential of urn graves. The urn fields are more flexible and appear like embroideries in the traditional graveyards. Here again, one sees how Sæland composes vegetation, paths and graves. In addition to the master plan, plans for each grave field are presented with proposals for planting design and the size of gravestones. This ensures that the cemetery appears as a unity.

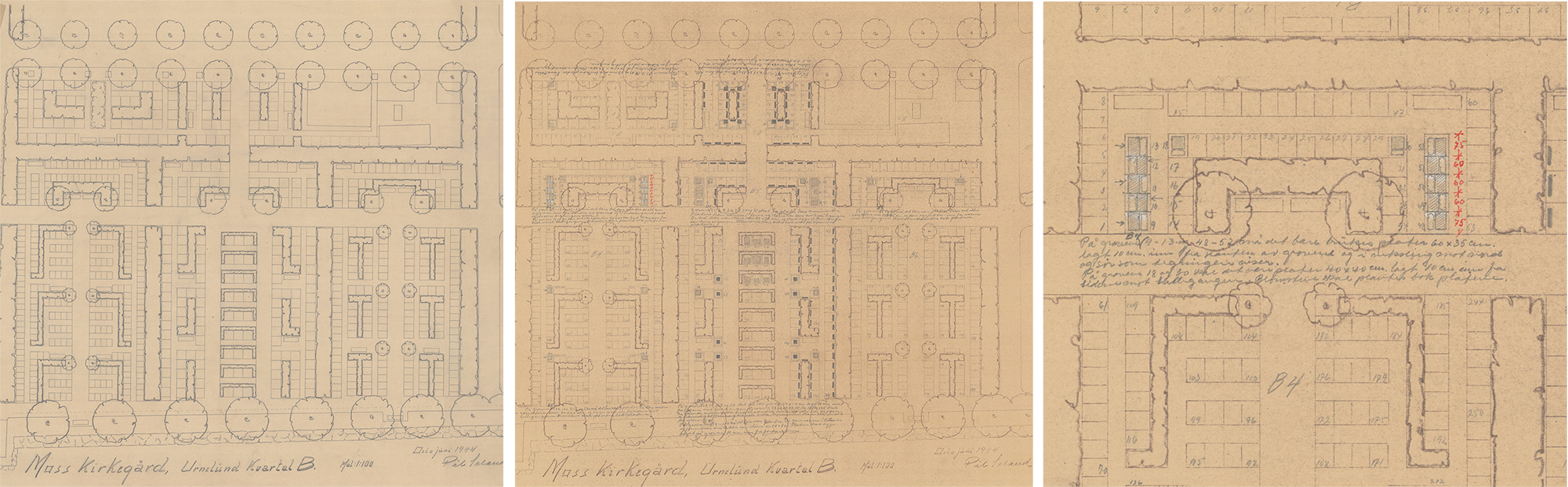

Details of Moss cemetery (1944) shows how Sæland composes vegetation, paths and graves.

Details of Moss cemetery (1944) shows how Sæland composes vegetation, paths and graves.

In his position as a garden architect and later as a cemetery consultant, Sæland traveled extensively to promote a good cemetery culture. During these travels he held numerous lectures or interviews, and some of the manuscripts are kept in his collection. In these lectures he provided practical advices in the planting of the individual graves. If one cannot afford to plant the grave with flowers every year, they can use perennial plants such as Sedum, Lysmachia, Vinca minor, Antennaria dioica or Hedera helix. Those who want to get more variety can use different types of flowers (Begonia multiflora, Viola, Lobelia, Tagetes, Asters and Antihirrnum), bulbs (such as crocuses, snow bells and tulips), perennials (such as Viola cornuta, Phlox, Peonia and Astilbe) and low creeping bushes for example, Cotoneaster horizontalis and C. precox, Lonicera pileate, small Cytisus, and low Berberis (Sæland 1940).

Sæland also has recommendations for the areas with long winters and snow: it is important to cover the graves with evergreens in autumn; do not tidy graves when the snow has fallen. Spruce, pine branches, juniper, clover, red currant and reindeer moss are the decorations that belong to the winters in Norway. Sæland recommends not to use flowers prematurely, “It’s a sad sight to see the greenhouse plants freezing in the snow.” Wintergreen plants that give good expressions in winter are Hedera helix, Vinca minor and Asarium (Sæland, undated manuscript of a lecture, ILA archive).

Proposal for Tjensvold cemetery in Stavanger (end of 1950s), not realised

Proposal for Tjensvold cemetery in Stavanger (end of 1950s), not realised

Planning and designing cemeteries is considered an extra challenging task. It combines functional and, to the highest degree, technical requirements with emotions and symbolism. Even professionals tend to push “the cemetery into the periphery of our area of interest. It is often seen as a necessary evil”, said by Karen Reistad in the 1960s, “if it is acknowledged that the cemetery belongs to a society’s culture, a deeper understanding of the cemetery must be adopted” (Reistad 1960).

Today, such challenges have not diminished. The re-establishment and expansion of cemeteries is one issue. In addition, especially in cities and towns, several nearly one-hundred-year-old cemeteries functioned as living cultural heritage, parks and recreation areas are under continuous pressure. Today’s knowledge, even in the academic communities, is far too weak to recognise and carry such values in future development plans.

In addition to good planning and craftsmanship, regular maintenance is the key to ensuring the quality of a cemetery. “It is the maintenance that shows that the life of the dead continues in the memory of the living. It is a beautiful message that life is stronger than death” (Sæland undated manuscript, ILA archive).

References:

Collection Pål Sæland, Historical Archive of Norwegian Landscape Architecture (ILA Archive)

Fylkestidende for Sogn og Fjordane (newspaper), 09.07.1954.

Jørgensen, Karsten. Kirkegården som speil for norsk landskapsarkitektur. In: Byggekunst 1995.

Moen, Olav. Gravplasser og kirkegårder i Norge. In: Norsk gartnerforenings Tidsskrift 1922.

Reistad, Karen. Almindelige regler ved anlegg av hager. In: Form og Flora 1937.

Reistad, Karen. Book review «Der Friedhof. Gestaltung, Bauten, Grabmahle» Otto Valentien & Josef Wiedemann. In: Havekunst 1963.

Sæland, Pål. Kyrkjegardane og gravene. In: Norsk Hagetidende 1931.

Sæland, Pål. Grav og kirkegård. In: Form og Flora 1937.

Sæland, Pål. Interview in relation to horticultural exhibition in Oslo 1938.

Sæland, Pål. Anlegg og Stell av gravsteder. In: Lommealmanakk for Gartnere og Hagebrukere. Norsk Gartnerforeningens Forlag 1940.

Skadsheim, Arne. Våre Kyrkjegardar i eit tidskifte. In: Norsk Hagetidende 1946.