This article invites the reader to think about how archive material can be used in the teaching of freehand drawing for landscape architecture students. We hope this provides inspiration for the education of future landscape architects.

Freehand drawing vs digital drawing aids

Today, the society and the discipline advocate computer-aided design in the profession of landscape architecture. A landscape architect can hardly survive in an office today without any knowledge of 3D-digital programs, Geographic Information systems or software application for image editing and photo retouching. In the School of Landscape Architecture at NMBU we see how important the freehand drawing is for creative processes, for understanding the site and for relating the designer to the space. Through freehand drawing one can emphasize the body’s central role in perception of the surroundings and in the drawing process (Montarou 2018). The landscape architecture program at NMBU offers courses in freehand drawing (in addition to courses in using digital programs and tools). The artists and teachers responsible for freehand drawing are also involved in larger studio courses, where they supervise students in various design projects.

Drawing techniques and archive material

In the autumn semester of 2019/2020 the freehand drawing teaching group tried a new approach in an undergraduate course for landscape architecture students. The idea was to look at historical drawings from the Archive of Norwegian Landscape Architecture and see how former students have designed and drawn a plan.

Historical drawings have already been used in learning drawing techniques at other universities, where the main focus is on learning drawing techniques with digital tools. Students started from vectorizing and digitizing hand-drawn plans and overlaid them with plans of the site using current open-source data maps. In addition, they were also asked to colour black-and-white photocopied historical drawings, or to redraw them with AUTOCAD (in their technical course ‘transfer hand-drawn designs into digital drawings’), or to translate historical drawings into 3D models (Krippner, U; Lička, L; Wück, R. 2019). Different from this, we (School of Landscape Architecture at NMBU) wanted to test how historical drawings can support the learning of freehand drawing techniques, since in the field of landscape architecture the focus on handwriting and hand drawing is gradually disappearing.

Exercises for students

Undergraduate students (in this case first year students) lack basic knowledge about the discipline’s history. Therefore, we avoided to overload them with a long introduction to the history of landscape architecture. Instead, we carefully picked some old plans from student projects in the Archive and presented them in a seminar room. These plans were drawn in 1920s, 30s, 50s and 60s respectively. Students were given several tasks while observing these plans, for example to look at composition principles and the use of symbols in the plans. We also gave them the task to interpret a 2D drawing into a 3D perspective, through which to develop the consciousness of space. The overall objective was to get knowledge and to be inspired by historical drawings from the Archive.

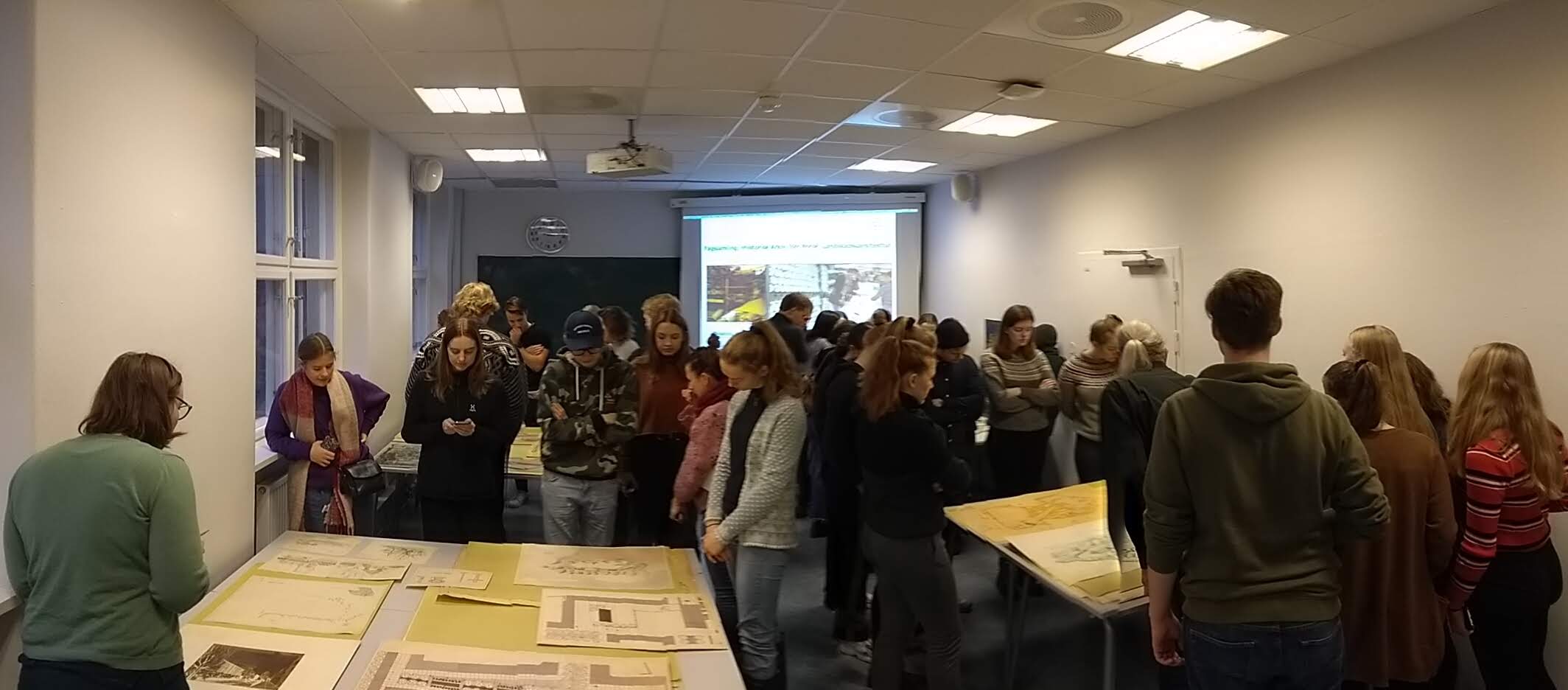

Students are looking at the various plans from the 1920s, 1930s, 1950s, and 1960s

Students are looking at the various plans from the 1920s, 1930s, 1950s, and 1960s

Tasks for the students:

- Choose a plan from available reproductions and analyze / understand how the drawing is composed. Use transparent paper to draw over and comment on how you perceive the characteristic of the drawing.

- Find composition principles, such as symmetry / asymmetry, repetitions / patterns, rhythm / equilibrium and so on.

- Focus on the use of symbols: how are trees, shrubs, lawn and other elements of the park / garden presented in the drawing? Try to emulate these to learn how they are done and get yourself a form-vocabular for your own plans in the future.

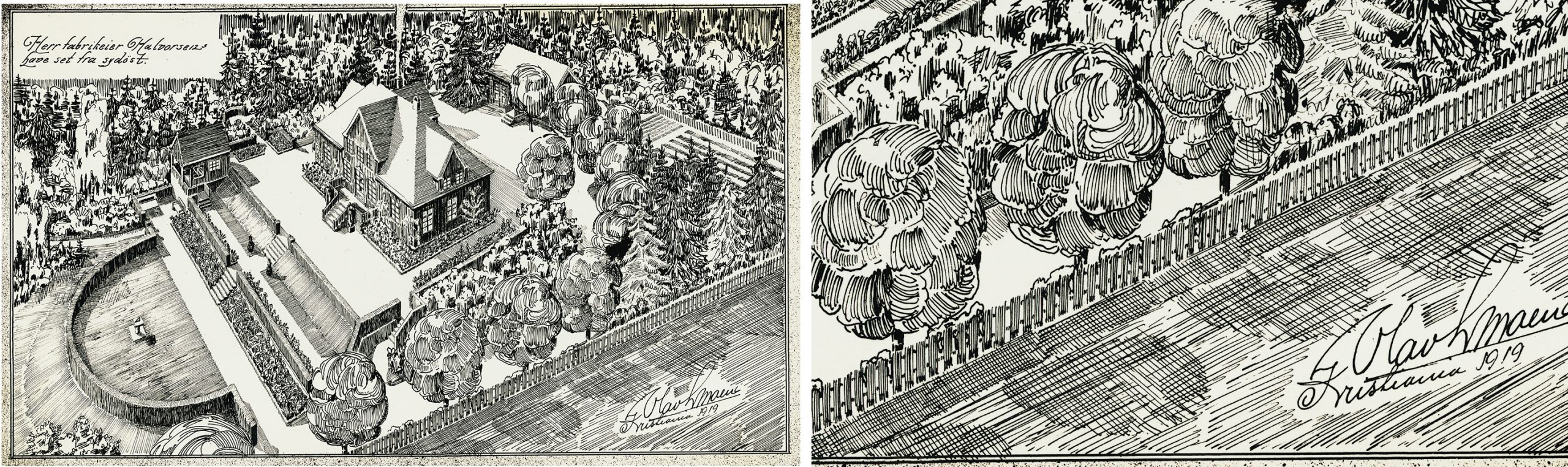

Scratches defining the direction of the shape. Ink drawing. Trees drawn with ink define a room in the plan/perspective

Scratches defining the direction of the shape. Ink drawing. Trees drawn with ink define a room in the plan/perspective

- Choose sections from a plan and try to draw one or two perspectives showing a space sequence, a la Gordon Cullen, by imagining the space freely and by a spatial interpretation of the plan.

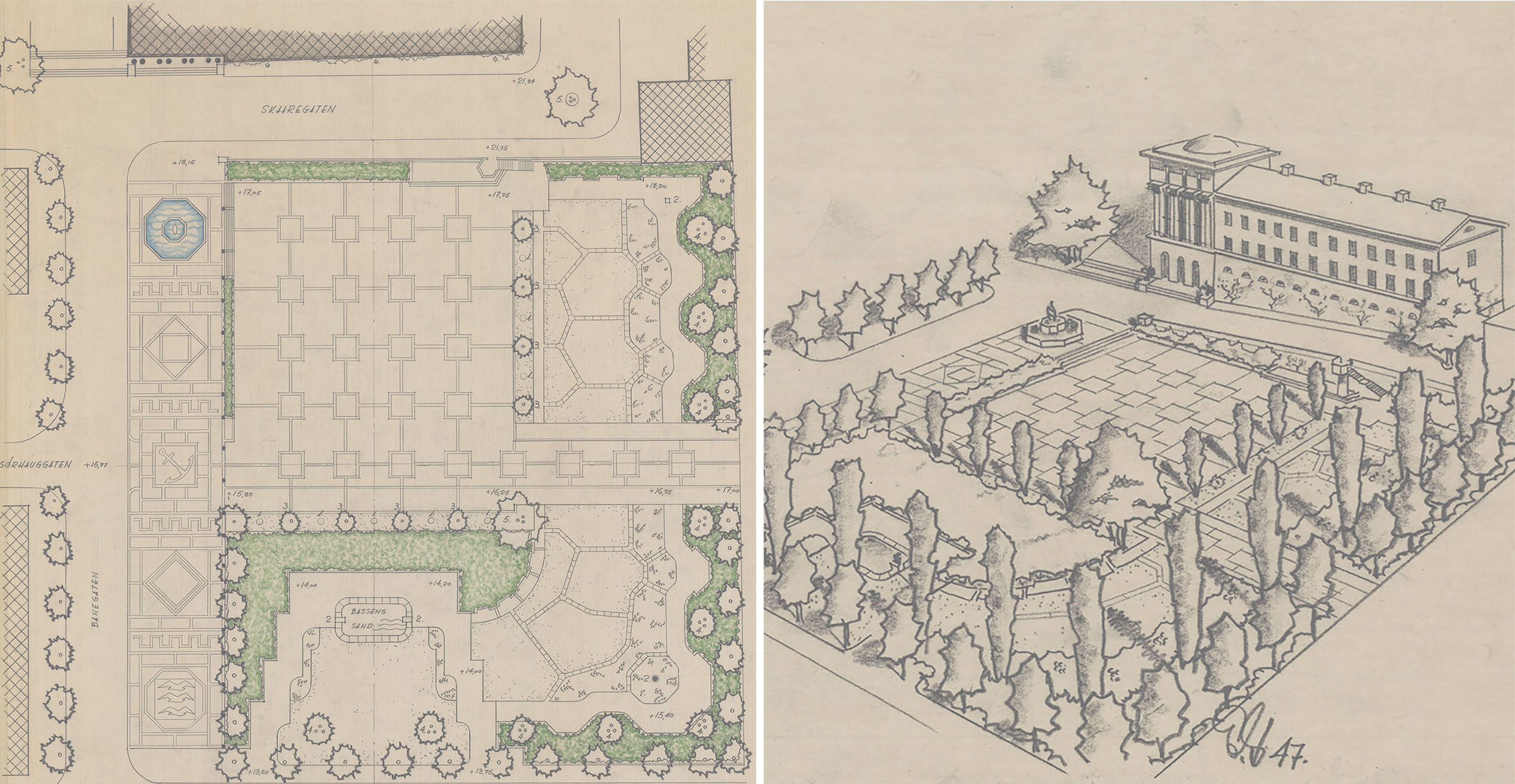

From a complete draft to a contradiction/reverse proposal drawn both in plan and perspective. Example shows the City hall park of Haugesund from 1947. Eyvind Strøm

From a complete draft to a contradiction/reverse proposal drawn both in plan and perspective. Example shows the City hall park of Haugesund from 1947. Eyvind Strøm

- Study the plan and photos of a park in Oslo and draw a contradiction proposal by changing vegetation and pavilion type for example. Try to be radically different from the original.

Plan and photo of a park in Oslo. Based on this example the students were asked to draw a contradiciton proposal by changing vegetation and pavilion type. Torshovparken 1937. Eyvind Strøm

Plan and photo of a park in Oslo. Based on this example the students were asked to draw a contradiciton proposal by changing vegetation and pavilion type. Torshovparken 1937. Eyvind Strøm

The experiment with this group of undergraduate students has clearly shown that archive material can be an innovative and effective teaching tool. It gives inspiration and even influences the design process itself. By decoding the hand-drawn plans, the students got a better knowledge of the design principles. Comparing and analyzing plans from different periods led to an expanded understanding of the projects’ contexts. By re-interpreting and re-designing the students better recognized the designers’ intentions. The students understand various and creative ways of presenting a project in a plan or perspective. They see in detail how forms/shapes are created in historical drawings. By going through materials from different periods one can also trace the different trends and fashions in visualising project ideas. Such experiences brought students a different understanding of space and form and encouraged them to reflect on the role of the designer/landscape architect in the project.

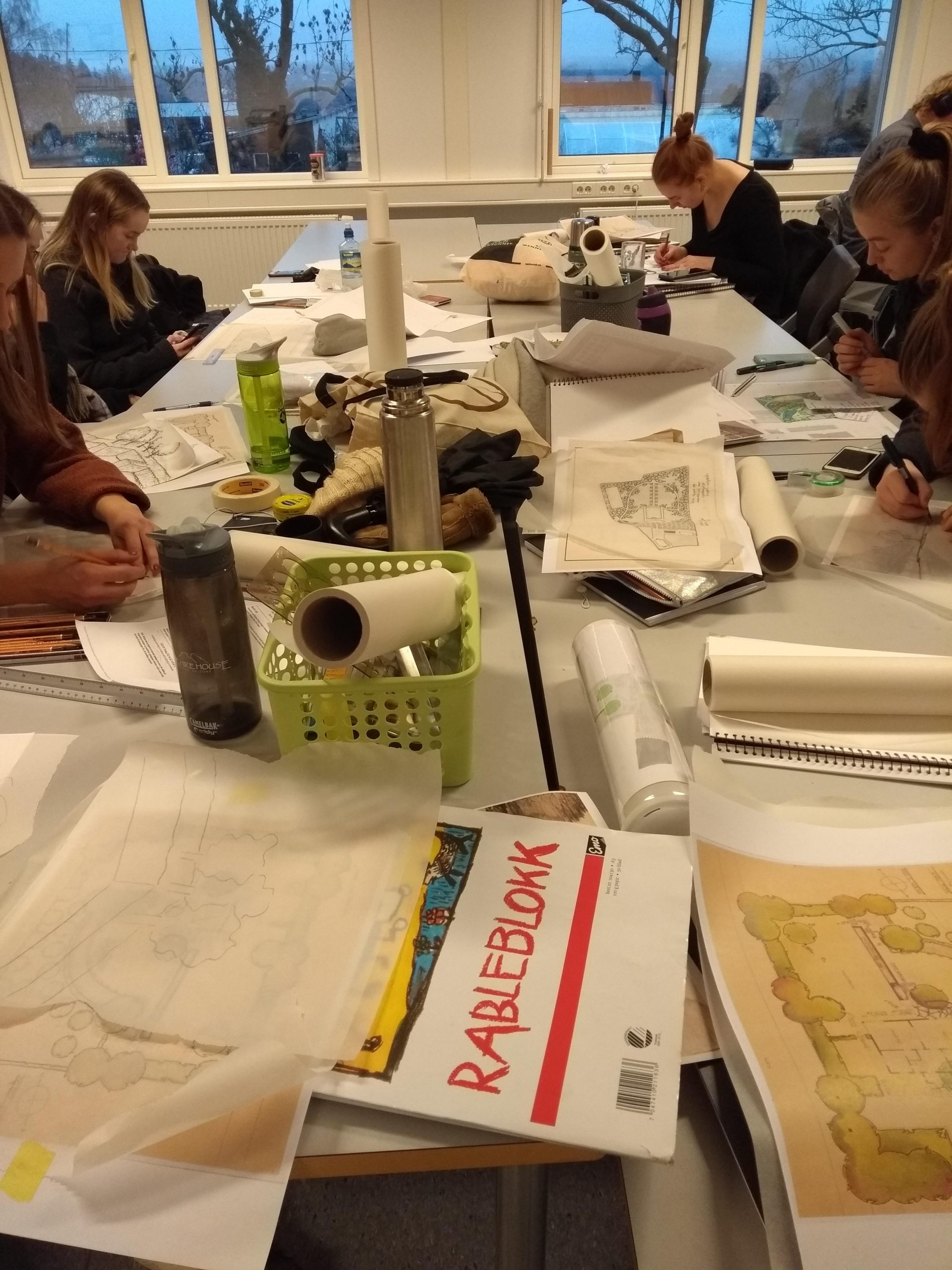

Students working with the tasks

Students working with the tasks

This experiment opens a ‘light’ way to approaching history. It might be a good supplement of the landscape history courses, which are ‘heavy’ and difficult for students getting a good insight into. In addition, archive material contains local/regional projects that students have knowledge of or feel close to. Therefore, the learning of such projects not only improves the students’ drawing skills, but also raises their awareness of understanding the history and heritage values of a place. It is hoped that students can also bring such awareness to other courses at both undergraduate and graduate levels. Furthermore, if we encourage students to use archives, it may increase the potential of them using archives in their future careers. (More about the importance of the archives see The Memory of a Discipline).

Various and creative ways of presenting a project. Freehand drawings from the 1950s and 1960s

Various and creative ways of presenting a project. Freehand drawings from the 1950s and 1960s

Feedbacks from students

Most of the students felt that the tasks were rather challenging, but intriguing. They were all inspired by the historical drawings, especially the different ways of writing, shaping and coloring. Only one of a group of 50 students admitted that the “motivation was not on the top”. The fact that the historical plans being drawn by students helped our students today find connection with these drawings. Not all projects are “perfect”, but they show that hand drawing qualities can hardly be reached by digital drawing aids today. The students also observed how relevant freehand drawing is for landscape architecture profession and discussed if a project presentation had really caught the main features/the overall design concept. Students admitted that historical plans opened different ways of reflecting landscape architecture projects.

Students also pointed out that computer-aided design is important, but those modern tools are a little limiting: “With a pencil in your hand and a blank sheet you can create anything.” Another student pointed out: “Because of the digital world, freehand drawing is even more important.” By using freehand drawing techniques combined with archive material, students started a creative process, where they experienced and perceived the surroundings in a different way. Historical drawings (especially the presentation of symbols, colors and shapes) give students more vocabularies to interpret a site and to present their own projects in future. As one student said, working this way is “freer, more esthetic and more vibrant”.

Historical drawings give the students more vocabularies to interpret the site and to present their own projects in future

Historical drawings give the students more vocabularies to interpret the site and to present their own projects in future

This article was written in a collaboration with researcher Lei Gao and associate professor Christian Montarou.

References:

Christian Montarou (2018): Hvordan øke bevissheten om den førspråklige dimensjonen av det kroppslige nærværet i tegningen? In: formAkademisk 11, no.3.

Krippner, U; Lička, L; Wück, R. (2019): Learning from history: integration an archive in landscape teaching In: Jørgensen, K; Karadenzi, N; Mertens, E; Stiles, R, Teaching Landscape: The Studio Experience, 214-225; Routledge, London ; ISBN 9780815380559).