Written by Erika J. Rojas, PhD Fellow, Noragric.

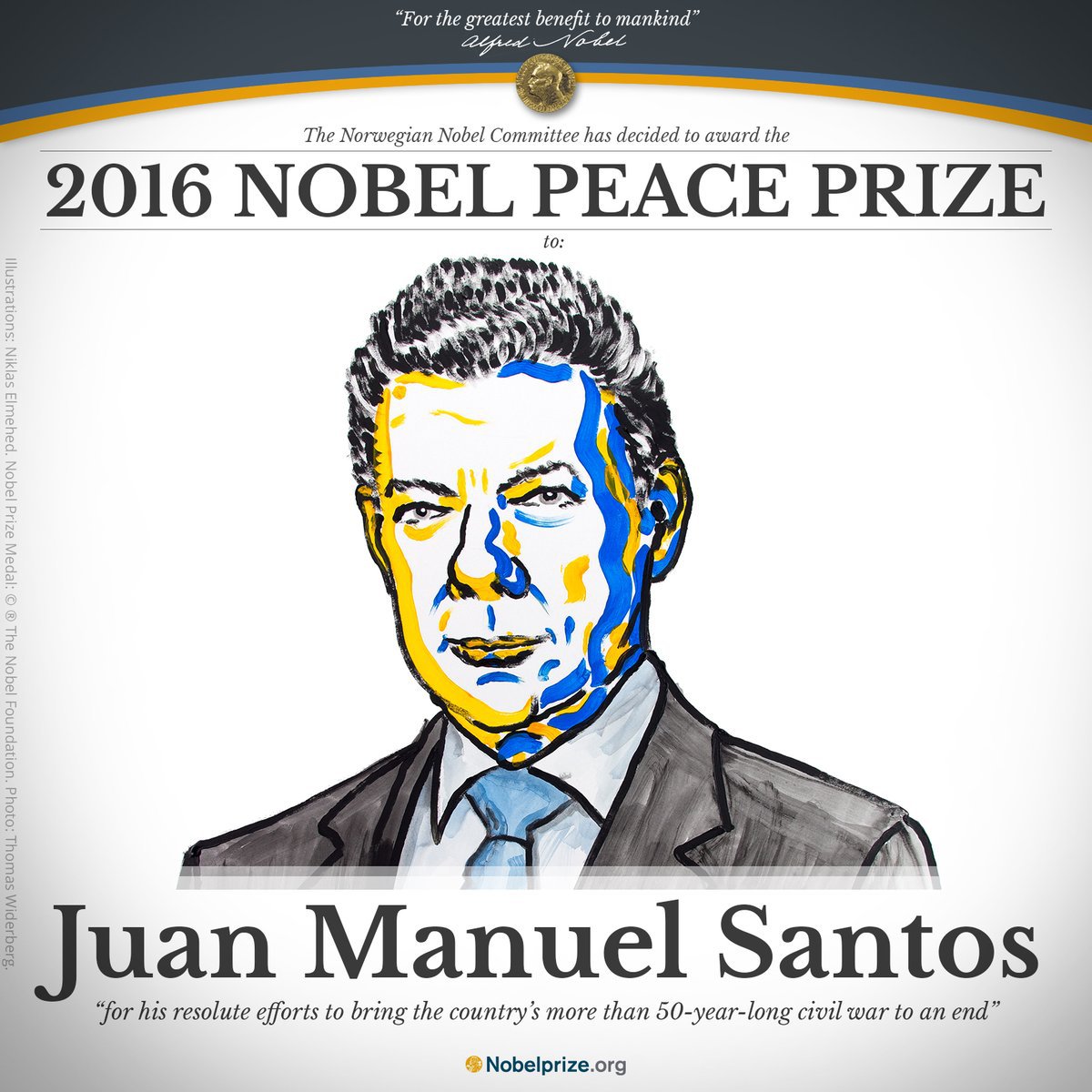

What Colombia has experienced during the last weeks could be part of the ‘magical realism’ that Gabriel García Márquez expressed in his literature, reflecting a reality that has hints of the surreal as beauty and fear cohabitate side by side and express themselves almost simultaneously. In this sense, Colombia has experienced an emotional rollercoaster, a political polarization and a strong mobilization since 2nd October, when, in a tight ballot, Colombians voted to reject the Peace Accords signed one week before between the government and the FARC-EP. On 7th October, Colombians experienced a burst of hope and international support when the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to the president Juan Manuel Santos for his efforts in the search for a peaceful resolution of the armed conflict. This scenario can have multiple interpretations and the accent on the positive or negative tone varies with the analysis. As a Colombian and supporter of the dialogue and a negotiated transformation of the armed conflict, I aim to present a positive – but realist – panorama. As a social scientist researching communitarian reconciliation processes and the construction of a post-conflict society, I seek to understand the Colombian context, and to highlight the existence of those peace and reconciliation spaces amidst the polarization in the country, in order to show their relevance in the current scenario. In this sense, it is important to analyse what happened in the plebiscite, what a political polarization means, and what the implications of the Nobel Peace Prize are for the future of the Peace agreement.

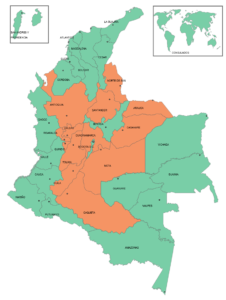

Let’s start with some numbers. On 2nd October, 6,431,376 Colombian citizens voted ‘NO’ to the Peace Agreement, versus 6,377,482 that voted supporting the agreement. With such a tight margin, it is easy to say that there is great polarization in the country between supporters and detractors of the current Peace Agreement. In this election, the people that voted in support of the Agreement are located in those areas that have been highly affected by the armed conflict, on the periphery of the country, while the ‘no-voters’ are mainly located in the cities and the centre of Colombia (click map to enlarge).

During the week after the plebiscite, Colombians got to learn about the mechanisms implemented by the ‘no’ leaders in their campaign, and this realization brought not only more disappointment but the clear notion that many of the people that voted against the Peace Agreement were misinformed about its contents.

It is important to see, however, that only 37.43% of the Colombians that could vote did so in this election, meaning that the majority of Colombians did not use their right to vote. Therefore, the discussion cannot only gravitate around the supporters or detractors of the Peace Agreement, but should include those who refrained from voting. Reasons for this abstention are historical; low political participation (32-50% according to the National Civil Registry) may be related to low levels of political trust – perhaps people perceive their vote cannot make a difference. In this sense, the results of last Sunday´s plebiscite present a reality in Colombia that reflects a need to bring the political debate close to the people and their day-to-day reality. In summary, the high level of abstention and the close but higher number of votes rejecting the agreement in the plebiscite, negatively affected the political support and legitimacy that the President was seeking for the Peace Agreement, thus creating a difficult scenario for its implementation.

Does this mean that the people in Colombia do not want peace? No. In fact, the day after the plebiscite the country woke up to a bitter taste of sorrow and guilt regarding the low percentage of voters. Polarization was expressed through different channels and people’s frustrations were voiced across the land. The leaders of the ‘no-vote’ based their campaign on the need to review the agreement and the possibility of a new negotiation that would address the concerns of the opposition related to justice, land distribution and political participation. The day after the plebiscite, many civil society organizations, students and other citizens demanded the opposition to present their proposed points for negotiation, and called for the different parties to sit together and discuss what could be done to save the peace process.

In the course of a week, the people of Colombia mobilized themselves to claim national support of peace. It became apparent that Colombians want peace but are unsure of how to implement it. Thus, the political discussion that had been nurtured in academic and institutional spaces jumped into the streets, into the cafes, the classrooms and the office hallways. People were in shock. They began to gather in a call for the peace process to continue; a silent march was started by youth and university countries in recognition of victims of the conflict, first in Bogotá, then across the country. And they continue. Since the first march was organized on the Wednesday after the plebiscite, there have been marches almost every day all around Colombia and in cities around the world in support of the Colombian Peace Agreement.

In this scenario, the political debate that started four years ago with the peace process has become stronger and louder since the plebiscite. It has incorporated an ethical element that was not visible enough before the plebiscite, which addresses the need for recognition. In the massive street-demonstrations, a unifying thread has been the acknowledgement of the victims of the armed conflict, their longing for peace and their right to live without the anguish caused by war. Encouraged with the support, afro-descendant and indigenous organizations, two of the most victimized groups that politically support the Agreement, demand its prompt implementation in their territories. Additionally, this pro-peace political mobilization is calling for the possibility to use direct participation mechanisms such as open councils in the Colombian constitution, to support the implementation of the current agreements.

As many say in Colombia, this might have been the most politically agitated week in decades, and people that were political indifferent are waking up to the call to unite voices to support peace. From this perspective, it could be easy to think there is a good chance to revive the peace agreement and validate it. The political reality of the country is, however, more complicated, with many parties now in the conversation. Therefore, even when civil society (students, victims’ organizations, indigenous and afro-descendent groups, and business representatives) has put aside its polarization in favour of peace, mobilizing and demanding an inclusive and efficient negotiation between the political parties to save the peace process, the opposing parties still have to come up with proposals to negotiate the current Peace Agreement. This moment in history has been referred to by the historian Marco Palacios as a ‘Political Theatre’. It seems that whilst the main roles are taken by politicians, this time the spectators are willing to join the play.

At the end of the week, on 7th October, the Nobel Peace Committee woke the country with the news that the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Juan Manuel Santos for his tenacity in the search for a negotiated end to the armed conflict and the possibilities for peace in Colombia. Additionally, the committee stated, the award was directed to the Colombian society for its continuous search for peace in the midst of conflict. In other words, this Nobel Peace Prize may be understood as a recognition to those individuals and organizations that have worked for the construction of peace amidst the armed conflict, in which victims’ organizations have played a major role, giving examples of reconciliation. It may also be a recognition of the transformation of the institutional narrative around the armed conflict and the opposition in Colombia, promoted by President Santos, which recognized the political foundations of the guerrilla struggle and opened the possibility for a negotiation that ended the idea of achieving power by military means.

News of the Peace Prize was thus received as a festive announcement in Colombia, and was perceived as an oxygenation for Santos and the Peace Process after a week of ups-and-downs. It is a statement of international political support that stresses the importance of the peace negotiation and the need for its continuation. Many things are at stake after the results of the plebiscite, including international support, both economic and political, and the role of the UN’s Verification Mission in Colombia. The prize emphasizes Santo’s will for peace and his commitment to the process and all that it includes. It is thus a direct call for Santos to honour this recognition and for the Colombian society to support it.

Colombia is now experiencing a new mix of hope, raised by increased civil mobilization, and uncertainty. At this moment, anything can happen and the opposition is willing to negotiate their points of disagreement with the document signed by the Government and FARC. Though Alvaro Uribe Vélez, leader of Centro Democrático and one of the political representatives of the ‘No-campaign’, and Marta Lucía Ramírez from the Conservative party, have presented some discussion points, the opposition does not only include them but also the Christian churches that promoted the ‘No-campaign’. The problem is that this plethora of discussion tables around the Peace Agreement stretches the chances for efficient and inclusive negotiations, making it difficult to come up with new proposals to negotiate with FARC in the near future.

Whilst there is protraction and a lack of consensus in the political discussions, the citizens have not stopped their demonstrations and are acting together to legitimize a consensus for peace. Consequently, it seems that the only road Colombia wants to take is towards peace, with negotiations between the government and ELN (the guerrilla group still operating), announced to commence on 27th October in Ecuador. On the 11th October, the artist Doris Salcedo gathered 3,500 people to sew together the names of 2,300 victims of the armed conflict into a white carpet, covering the floor of ‘Plaza Bolivar’ in Bogotá. The performance was called ‘Sumando Ausencias’ (Adding Absences) and was a public mourning of the victims and a symbolic act for peace. And yesterday, 12th of October, Colombians are again using the streets as a platform to demand their right to peace and celebrate cultural diversity.

What will happen in Colombia remains uncertain. Nevertheless, current events in the country present a great possibility to construct a more inclusive and legitimate peace.

Erika Rojas is a Colombian PhD Fellow at NMBU. Her research interests are in conflict transformation, peace-building, security, gender and reconciliation. She is part of the EU Horizon 2020 project ICT4COP, Community-Based Policing and Post-Conflict Police Reform, in which she is researching the ‘re-definition of (in)security and community-based policing after reconciliation’.

Erika will present at a ‘Nobel Dinner’ hosted by Vitenparken and the Society of Doctoral Candidates at NMBU (SoDoC) in November.