Written by Lauren Guido, Student on the Noragric Bachelor program in International Environment and Development Studies.

A few days ago, my team of three (from The Innovation Effect) and I stood in front of 200 business leaders at Oslo Innovation Week, presenting our sustainability research and demands for Orkla. Five years ago, I would have never imagined myself passionately discussing my work for this (or any) multinational food and cosmetics company, in, of all places, Norway.

I am young millennial. I prefer coconut oil over lotion and I use herbal medicines before resorting to prescriptions. I read labels and have conversations about food systems on first dates. If tweeting to Michael Pollan and binge reading peer-reviewed sustainability articles isn’t enough, I’m not sure what it is.

Orkla and other major companies face problems from people like me. My generation demands more sustainable and greener products from them. We don’t just want trendy and expensive health food, but a cultural shift. We care about what we put into our bodies and on them, not just when we have extra money to spend, but all the time.

Throughout the years, I’ve volunteered, interned, studied, and travelled abroad in search of understanding what the food and sustainability sector looks from various angles; the facts and figures on why it’s important to live a green lifestyle have been ingrained in me since childhood. I have been involved with some amazing organizations that want to change the system. Despite great ideas and intentions, non-profits and NGOs spend an inordinate amount of time focusing on securing funding than actually implementing their vision. Even after years of working inside organizations, it is difficult for me to determine how to achieve impact and get results without going over the fiscal tipping point. After all, isn’t it the impact and results that matter when it comes to sustainability?

In my course of study, International Development and Environmental Studies, big companies are often seen as the bad guys, and rightly so. Orkla essentially controls the food market in Norway, as do companies such as Kraft and Nestle in the States. Companies such as Orkla are willing to change; they are putting their goals into action by setting up corporate social responsibility programs (CSR) and sustainability departments – but it’s not enough and they know it.

A team of Orkla employees, ‘the rebels’, set up the particular project I’m working on, called ‘Young Sustainable Influence’. The focus is on researching and finding solutions on how Orkla can appeal to the next generation of consumers in a sustainable way.

At first, this may sound like green-washing: How can a company really change? After all, Orkla sells 8.5 million products every day in Norway alone. That’s quite an impressive number, especially since Norway’s population is only 5 million.

I used to believe radical change and impact could only happen by outsiders fighting the system, but in reality if the system is going to change, it will change from within. When I think about the impact that a simple and small change to any part of the Orkla supply chain could have on the planet, I am blown away. I get goose bumps when I think about what effect a dozen simple changes in this supply chain could have on the globe.

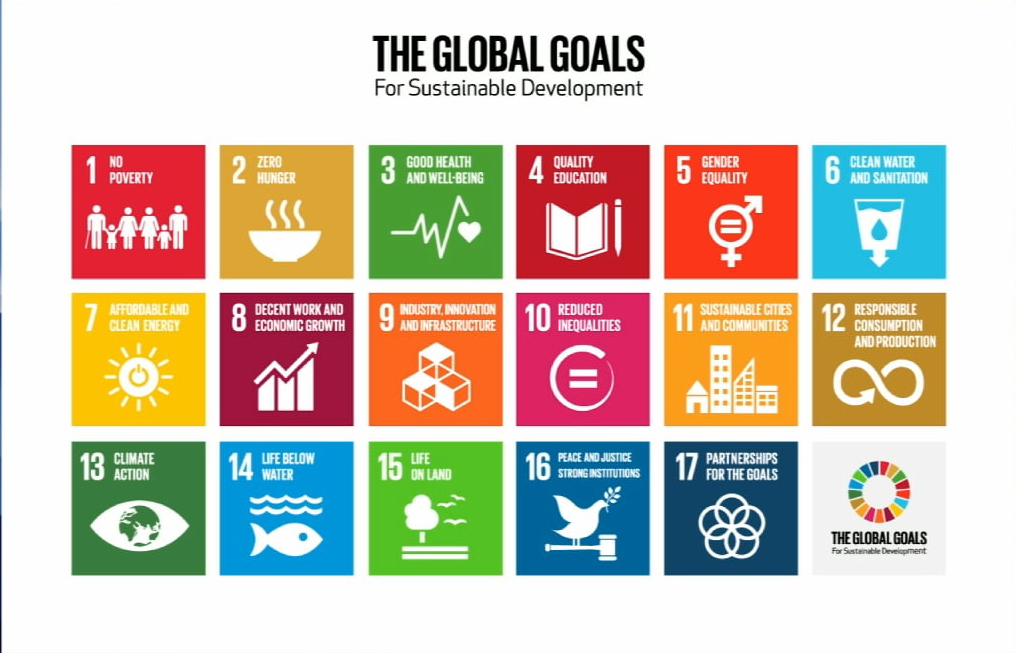

The United Nations has set out 17 ambitious global goals called the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to be reached by 2030. Examples include ending global hunger (goal 2) and ensuring sustainable consumption and production patterns (goal 12). I wholeheartedly believe that it is possible for the world to reach the United Nations SDGs in the next 14 years. This will only be true if there is a paradigm shift in the way twenty-first century change-makers think about how to solve the large- scale social problems that our globe faces.

The key to this shift lies in having perspective. For myself, I choose to effect change from the inside rather than continuing to question from the outside.

This paradigm shift approach is what I believe will make the most impact and solve the most problems. Rather than starting from the ground up, work from within. Treat the problem at the source.

Lauren Guido is a Bachelor student at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences. She was part of a group of students in Norway to recently feature in an article on Norway’s environmental policies in The Guardian.