Olav B. Soldal offers his impressions from a trip to Costa Rica earlier this year where he was part of an NMBU field course working with a community struggling to resist the pressures of the dominant pineapple corporation in the region.

Costa Rica, known to most as a land of lush rainforests and a biodiversity hotspot, is at a crossroads. The country of about 4.9 million people has experienced rapid economic growth and urbanization over the last decades, and is now considered one of the most developed countries in Latin America.

The country is internationally renown for its remarkably peaceful history in a region otherwise marked by violent conflicts and political upheavals, and the abolition of its armed forces in 1949. Since a largely peaceful revolution in 1948, the country has avoided the disruption of democratic due process. Yet today, Costa Rica’s economy is fragile, with government debt at record levels, and political backlash to recent VAT adjustment and growing food prices. In common with other countries in the region, Costa Rica is also feeling the pressure of a changing climate, with longer dry seasons and more extensive forest fires.

Despite ambitious policies on climate action, its role as a world biodiversity hotspot and its efforts to regenerate forests, Costa Rica is struggling to conserve its ecosystems. Agri-business, in the shape of plantation production with the export of tropical produce such as coffee, bananas and pineapple, is the mainstay of the Costa Rican economy. Pineapple now tops the list of the country’s exports, surpassing the historical dominance of bananas. With its economic dependence on this sector, growing pressure is being placed on large swathes of Costa Rica’s rainforest ecosystems. The multinational corporations that hold a firm grip on the country’s primary production sectors are accused of increasingly malign political interventions in order to maintain their favourable conditions. A large proportion of Costa Rica’s lower income population work on the plantations, and politicians tout the importance of the sector for employment opportunities.

Has the pineapple industry become bitter sweet?

There is an inherent contradiction between ecological conservation and expanding plantations in Costa Rica, and the pineapple is at the centre of it all. As more attention is given to deforestation caused by encroaching plantations, environmental organizations have been putting increasing pressure on wealthier nations to limit their import of these tropical products. The Costa Rican government has vowed to protect and reforest up to 60% of its land area and reverse the “degradation of marine and terrestrial ecosystems” by 2050. At the same time, it has committed to deliver ‘green growth’ and to stimulate its growing plantation economy. Whilst being a steady source of income and positive to the Costa Rican terms of trade, has the pineapple industry become rather bitter sweet?

Pineapple farming and land-use conflict

In June 2019, I participated in a practicum course jointly run by NMBU, the American University in Washington and the UN Peace University as part of their ongoing cooperation on research-based training. The specific purpose of the fieldtrip was to examine the roots of land use conflict caused by the expansion of pineapple farming in Costa Rica.

Pineapple has become Costa Rica’s largest export crop over a short period. It uses high quantities of pesticides and research has illustrated the negative impacts on ground water and on biodiversity. It encroaches protected and indigenous land and threatens forests. The social conditions of workers as well as those living around the plantations violate human rights (e.g., life, food, water). Pesticides flow into the drinking water surrounding plantations. Workers and community members report health impacts and birth defects.

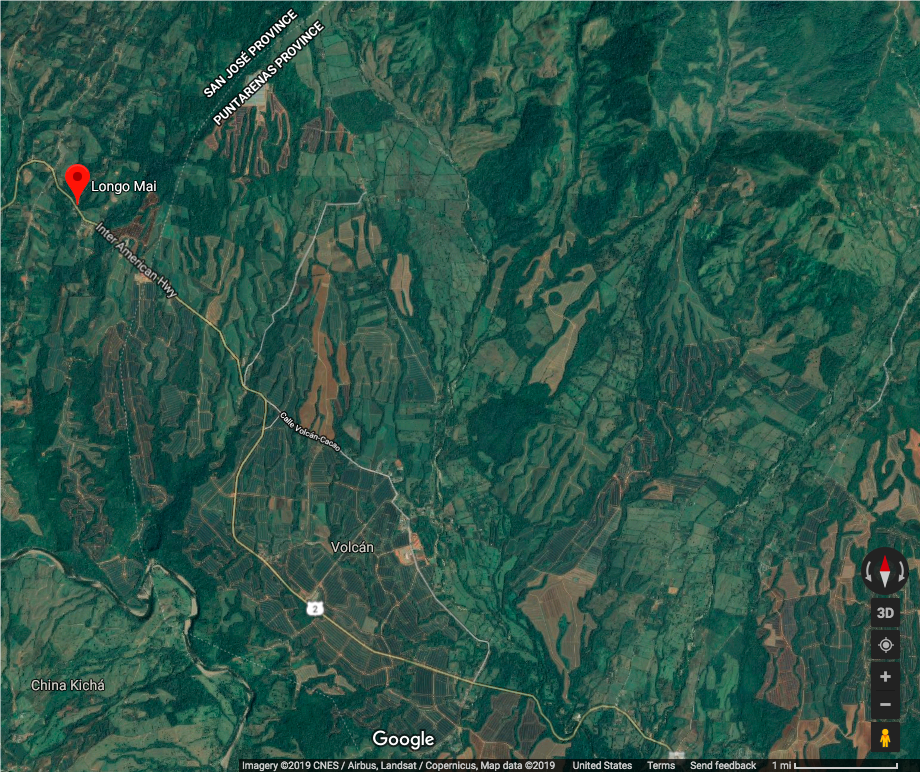

The focus of our study was the community development association of Longo Mai in southwestern Costa Rica. Through the practicum, we were primarily concerned with providing answers that could be of value to the community and its long-term autonomy, sustainability and development.

I was part of a group of students focused on health issues and environmental impacts related to pineapple production including how pineapple plantations have impacted land-use, ownership and economic opportunities in the region.

Why Longo Mai?

Longo Mai is a small, diverse community in the San Jose region region of Costa Rica, with residents originating from El Salvador, Nicaragua, Switzerland, Germany, and elsewhere in Costa Rica, including some of indigenous heritage. During the 1970’s, there was a great deal of civil unrest throughout Central America, as well as in Pinochet’s Chile. The Somoza family had been running Nicaragua as if it were a business, controlling the majority of the country’s production and export. In 1978, the government of Nicaragua assassinated a conservative party critic named Pedro Juaquin Chamorro resulting in large protests, which were forcefully quashed leading the opposition to take to arms. In 1979, Nicaragua underwent a revolution led by the Sandinista movement against the Somoza regime. El Salvador also experienced a civil war between 1980 and 1992. Salvadoran armed forces committed human rights violations, including a number of massacres during the early 1980’s. It was to this backdrop that the Longo Mai movement in Europe decided to establish a community in Central America in 1979, to create a refuge for those fleeing persecution and civil unrest in the region.

An oasis in a desert of pineapple

Upon arriving in Longo Mai, my first impression was how pristine the nature and landscape was. The built environment blended into the forest, creating a unique, fresh micro-climate in contrast to the surrounding arid plantation landscape. Our interviews with community members soon revealed, however, that things were far from perfect in paradise.

Environmental contamination and loss of biodiversity

The community had experienced rapid change over the past two decades, mainly due to the ever-expanding plantations in the neighbouring landscape. There was an acute sense of biodiversity loss, perceived risks of harm from pesticides and contamination of aquatic resources. A study the by University of Costa Rica found traces of six different pesticides in the Terraba-Sierpe Wetlands located in the neighbouring municipality. There is also a sense that the ownership and use of the land is changing rapidly, perhaps most acutely in the neighbouring town of Volcán, where most smallholder farmers have sold of their land to large pineapple-plantation companies. Today, there are almost no smallholders left, expect for in Longo Mai, and almost no-one owns the land on which they work.

There is a schism between the generations when it comes to defining what is appropriate land-use and good farming. The older generation has a strong connection to the land and would prefer to work it independently, whilst the younger generation regard the plantation jobs as a good source of income and an important driver of economic development.

The shift to employment-based income has altered the lifestyles and social dynamics among people in the region, and many report an increasing reliance on imported goods. This shift has generated tension over land management, with more community members expressing doubt over land ownership structures as the land-use practices have changed with the generations. There is real concern in the community that the cooperative structure of land management is faltering under ever-increasing pressures from the plantation industry and public authorities.

Our own research indicates that the unique model of land ownership of Longo Mai, where land is collectively held and managed, has protected the community from encroachment by the pineapple company, PINDECO. In contrast to the neighbouring community of Volcán, land has not been sold off to the company, and the pastoralist lifestyle has been maintained. As a result, ecological impacts were seen to be significantly lower in Longo Mai.

Finding common ground

The community of Longo Mai faces a bumpy road ahead. Pressure from the authorities and plantation industry are unlikely to subdue in the near future.

When asked what characterises the identity of Longo Mai today, a common emphasis was placed on cultural pluralism, peace and environmentalism. Topics that represented disagreement amongst the community included tolerance, respect for the elderly, and increased involvement with the pineapple industry. Overall, we found that the values that people associated with the community stemmed from their motivations to move to Longo Mai in the first place; families who had come from situations of war and violence identified peace as the main value of the village and those who came to escape economic hardship emphasized the opportunities available in Longo Mai if one works hard enough.

Regarding aspirations for the future, the theme was largely the same across the community: Better schooling options, including for older children (Longo Mai only has a primary school), more teaching on organic agriculture, more solidarity between groups, and a more representative community leadership (not just Europeans and men, as one interviewee pointed out). Many also voiced concern for alternative economic opportunities, so that youth don’t have to leave the community to make a living.

By the end of our stay, we realized that the community was more or less unified in their desire to identify routes to a greener, healthier future.

I left Longo Mai with the realization that our research had revealed something unexpected. Despite the challenges faced by communities on the margins of pineapple plantations such as Longo Mai, it is still possible to conceive a peaceful and prosperous society, through dialogue and living in harmony with the natural surroundings.

This could be a lesson for the rest of Costa Rica, and indeed the Western hemisphere, as we all strive to find a balance between economic and ecological sustainability. While Costa Rica is a highly developed and peaceful part of a largely troubled region, it is also a country marked by high levels of inequality, corporate cronyism and political corruption. The Costa Rican rainforest represents one of the world’s greatest biodiversity hotspots – and mitigating global climate change hinges on succeeding in forest conservation. So, before we next indulge in a sweet bite of pineapple, we might first ask if the plantation economy that underpins it is just too hard to swallow.

Olav Soldal is a student on Noragric’s MSc programme in International Environmental Studies.